REVIEW: ‘Watercolors of the Acropolis’ at The Met

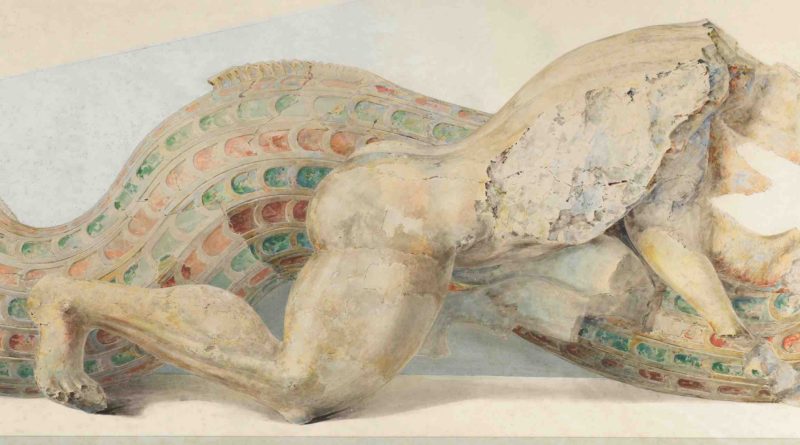

Image: Émile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924). Herakles Wrestling Triton, 1919. Watercolor, graphite, and crayon on paper. Length: 133-1/8 in. (338.1 cm), height: 38-1/4 in. (97.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dodge Fund, 1919 (19.195.5). Image courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art / Provided with permission.

NEW YORK — One of the first impressions that comes to mind when viewing the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Watercolors of the Acropolis: Émile Gilliéron in Athens is the sheer size of these drawings. Of the five renderings of the Acropolis, three of them span more than 11 feet, according to press notes. They snugly encapsulate a small gallery, offering viewers the chance to stand in the middle of the room and look around at the artistic mastery. With a squint of the eye, one may even be transported to Athens.

How these watercolor drawings came to be is quite the interesting historical tale. In the 19th century, when Greece’s ancient ruins were being explored and discovered, the world’s adventurers didn’t have photographic evidence to bring back to their home countries. What they relied on, press notes indicate, were meticulously crafted drawings and paintings.

That’s where Gilliéron, a Swiss artist, enters the picture. His life spanned a healthy 74 years, taking him from the middle of the 18th century to the 1920s. He drafted many architectural wonders, and of particular note are these Acropolis re-creations, made 1/3 to 1/2 of the actual size, which were acquired by the Met in the early part of the 20th century.

The depicted scenes are full of energy and common iconography of antiquity. There are two lions savaging a bull, perhaps the most graphic and visually stirring of the bunch. The bull lies motionless, buttressed by the symmetry of the attacking lions. It’s a scene of violence and sorrow, savage beauty and riveting artistry. Gilliéron sketches with graphite the areas that apparently were not found amongst the ruins — mostly the lions’ bodies.

Another offering features a three-bodied figure with a serpentine tail. This piece, like the others, clearly showcases the pediment nature of the architectural objects. The three bodies of the figure are assembled from tallest to shortest, left to right, mimicking the diminishing angle of the pediment’s triangular shape.

Working within the confines of a pediment structure is most evident in Gilliéron’s “Herakles Killing the Hydra of Lerna,” which presents a watercolor of almost the entire structure, simply scaled down for size. The artistic rendering offers Met visitors the best chance of experiencing the Acropolis’ wonders.

Perhaps the highlight of the exhibition is “Herakles Wrestling Triton,” mostly because of the intricate scales of Triton’s merman tail. The red and green pop off Gilliéron’s depiction of the architectural ruin, more than any other color in the gallery.

Helpful notes in the gallery and accompanying video provide insights into not only the history of the painter and the history of the Acropolis, but also the Met’s painstaking work at restoring the watercolors. For those looking for a deeper dive, the museum’s spring 2019 Bulletin offers many more historical and artistic insights.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Watercolors of the Acropolis: Émile Gilliéron in Athens is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through Jan. 20. Click here for more information.