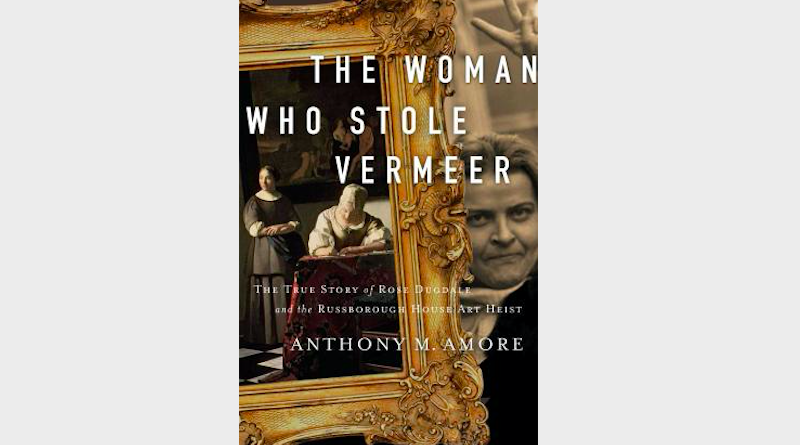

REVIEW: ‘The Woman Who Stole Vermeer’ by Anthony M. Amore

Image courtesy of Pegasus Books / Provided by official website.

The Woman Who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist by Anthony M. Amore is a fascinating history lesson that details the bombings, the hunger strikes, the politics and the violence in Northern Ireland in the second half of the 20th century. These tales of the not-too-distant past are seen through the eyes of Rose Dugdale, a British “heiress-turned-revolutionary,” who turned away from her privileged life of wealth and comfort to join the cause of Irish republicanism.

Dugdale’s story is almost too strange to believe, no doubt the reason Amore was attracted to the tale in the first place. Her life trajectory was anything but traditional, and what she ended up doing was both shocking and violent. As the title of the book suggests, the former heiress eventually became known as the woman who stole a Vermeer painting, in particular “Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid,” a beautiful example of the Dutch master’s talents.

What sets Amore’s text apart is that he takes what could have been relegated as an historical footnote (although some could argue that this art heist, the largest of its kind, is actually big news for the history books) and contextualizes it by describing the events that surrounded and informed Dugdale’s actions. As one example, there is a chapter about her visit as a young woman to Fidel Castro’s Cuba where she learned some of her revolutionary ways. There are passages about how she was taken in by the cause of Irish republicanism and fought for suspected bombers to be released from British jails and returned to Northern Ireland as political prisoners. There is a haunting explanation of the Bloody Sunday ordeal that saw protestors mowed down by security forces.

It still remains unclear after reading the book what exactly prompted Dugdale to take up her cause and steal the Vermeer (in addition to other high-priced paintings). Amore lays the historical groundwork and lets the reader decide what may have prompted her radicalization, and whether that transformation was sudden or gradual. There were a few people in Dugdale’s life that seemed to hold influence over her, but the counterargument is that Dugdale likely influenced them more than the other way around. There are her doting parents who never seemed to give up hope that she might return home one day (and hopefully not steal the family heirlooms again). There’s an early lover who was separated from Dugdale only after a lengthy jail sentence, and then there’s a later relationship that proved pivotal around the time of the Vermeer escapade.

Learning of these stories makes for an enthralling read, mostly because Dugdale’s actions are so notorious. Her criminality certainly stands apart because of its uniqueness — stealing a priceless painting is not an everyday activity — but it also fits into a larger historical picture of what happened in Northern Ireland in the latter part of the 20th century. These history lessons extend back a few centuries as well, thanks to Amore’s detailing of Vermeer as a painter and how “Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid” came to be.

There is no doubt that Dugdale makes for a controversial subject. If it were not for the art heist at the Russborough estate, her name may be lost to the history books, but because of that unusual, mysterious affair, readers have a chance to learn about these strange goings-on set amidst a larger narrative of struggle. The storytelling doesn’t sympathize with Dugdale — the allegations against her include hijacking a helicopter, dropping makeshift bombs and holding the Vermeer’s owners hostage, after all — but it does effectively detail an outsider’s connection to the I.R.A. and the seemingly no-limits lifestyle she was willing to lead.

The archival information gathered within these pages is thorough and thoughtful, no doubt aided by Amore’s career as director of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. He didn’t receive an interview with Dugdale, who is still alive, but the woman is brought to life through other conversations, newspaper articles and reflections from contemporaries.

What emerges is a controversial woman who led a life of criminality almost impossible to believe.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

The Woman Who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist by Anthony M. Amore. 272 pages. Pegasus Books. Click here for more information.