REVIEW: Combining fact, fiction in MoMA’s ‘Walid Raad’ retrospective

NEW YORK — The recently closed Walid Raad retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art offered a perplexing balancing act between the worlds of documentary reality and fabricated art. The Lebanese artist molds together history and fiction to tell multiple stories of lives ravaged by war and an alternative lens into recent memories and ongoing events.

The exhibition, which travels to Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art on Feb. 24 and Mexico City’s Museo Jumex on Oct. 13, is split between two expansive projects in the artist’s life. Scratching on things I could disavow, which filled the atrium at MoMA, is a multi-dimensional exhibit experienced by audience members as a walkthrough lesson in the complicated reality/perception of art in Lebanon and the Arab world. On select dates, Raad himself accompanied the public around the exhibit, offering a 55-minute performance on how to interpret the several constructions and convoluted maps.

Scratching is an art piece about art. As explained by Raad in a recent performance of Walkthrough, the artist was approached to join a collective of other artists. In painstaking detail, he outlines the institutional and financial framework of this organization and its higher-ups. His descriptions are highlighted by pictures, animated visual images, arrows criss-crossing one another, cut-out contracts and many, many words to absorb. At first, the connections seem too complicated to understand, the arrows seemingly pointing toward incomprehension. However, Raad’s ability to lay out the story — note: it’s difficult to tell what’s fact and what’s historical fiction — allows the audience to move closer to the material and consider his thesis of how art is funded, how it’s interpreted and the changes that occur on the institutional/global level.

In the performance, he makes some profound statements about how the artistic world, the economic world and the military world have uneasy financial ties. Rather than finishing his thesis, he decides to let these statements linger in the minds of those who are gathered, allowing the audience to fill in the blanks and consider the exhortations from multiple angles.

He eventually personalizes Walkthrough and talks about the prospects of his own exhibition opening in a new museum. At some point it becomes obvious that the artist has jumped beyond reality and entered the realm of fabrication, but the determination of his storytelling, the believability of his tone and the “facts” he uses as evidence all point toward a deeper meaning to consider. After a while, the truth of the matter doesn’t need to be proved; it’s a secondary consideration.

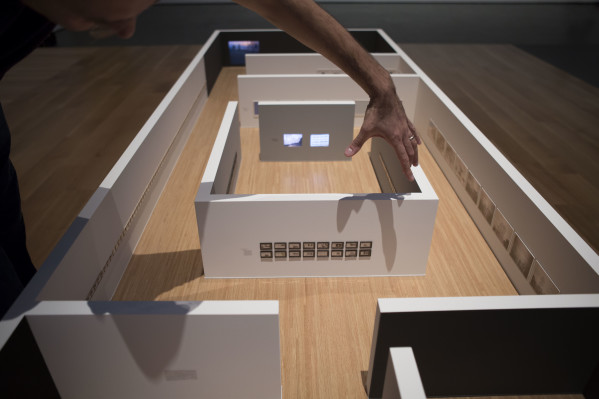

Raad talks about his exhibition being shrunk down to the size of a large dollhouse, and sure enough, his pieces are displayed on walls only inches high. The diorama has a strange poetry to it; Raad is able to look over his mini creations like a mythological god, a centaur able to view the maze from above.

The artist also talks about messages he has received from an artist in the future, the inability to express color in the future and the many connections circulating around his professional life. Walking through Scratching is an interesting experience, and it’s elevated to another level when the artist explains some of the visual displays.

The second part of the retrospective contains pieces from Raad’s project called The Atlas Group, which ran from 1989 to 2004, although some pieces extend beyond those 15 years. These photographs, videotapes, notebooks and lectures — all based on Lebanon’s recent war-torn history but still fictionalized — mold together real events with curious additions that augment their reality.

A series of photographs named Civilizationally, we do not dig holes to bury ourselves finds a man posing in front of several iconic European landmarks. From the Eiffel Tower to Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, the images have a “realness” to them but also a “changed” reality.

Another series of photographs, We decided to let them say, “we are convinced” twice. It was more convincing this way, shows a skyline ravaged by bombs and military scenes. Some of the images seem pulled from an old 8mm camera, while others are confounding in their abstraction (the four plane photos, for example).

Other photographs depict fictionalized objects like notebooks of Missing Lebanese wars and Already been in a lake of fire, which has a collage of cars and inscriptions. Some of the pieces are attributed to Dr. Fadl Fakhouri, who may or may not be based on a real person. Each time audiences shuffle past Raad’s pieces, they are given an Atlas Group description, which needs to be taken with a grain of salt.

Some of the most striking photographs on display include the I might die before I get a rifle series. Faces are out of the picture; instead, a solitary hand holds up a bomb device. They almost seem like morgue pictures or police evidence. Some of the hands are gloved, and the placement of the devices makes it seem like the photos are documenting what happened in the war and how it happened.

Everything in The Atlas Group seems to be quite large. Many of the photographs, which make up the bulk of the exhibition, measure more than 2 or 3 feet. Their size adds to their effect and instigate viewers to spend more time inspecting the balance between reality and fabrication. This is on perfect display in We are a fair people. We never speak well of one another, perhaps the highlight of the entire Walid Raad retrospective. Audiences look at architectural rubble and natural images, all seemingly un-doctored. However, after a few seconds (perhaps minutes), clues of Raad’s influence can be found.

Let’s be honest, the weather helped offers pictures scattered with colorful dots that represent the shrapnel realties of the Lebanese war. Among the videos on display are Hostage: The Bachar tapes (English version), which describes an alternative viewpoint of the infamous Lebanon hostage crisis 30 years ago. A number of sculptural objects at the beginning of the gallery space are apparently historical, but their faux shadows call into question their origin.

More than most contemporary artists, Raad couples an historical awareness with a plea to look closer and think differently. It’s not the most important (or interesting) facet that the artist’s work is fictionalized. As MoMA points out, the videos, photographs and displays are based on reality; they head in different directions and are not bound by the truth.

It does take time to appreciate the questions that inevitably arise after taking in Raad’s work. After his performance of Walkthrough, I needed to process the information slowly, trying to follow the many connections he brought to bear. When the artist stood before an extremely tall wall of framed colored prints, insisting the audience look closer at the colors and subtleties, the enormity of Scratching and the impact of the artist’s message came into focus. The same for The Atlas Group pieces, which offer a different take on Lebanon’s history, and by looking closer and thinking differently, one can see the connection between this Lebanese artist and the place of his birth.

Head scratching never seemed so engaging.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

- Walid Raad recently finished its run at the Museum of Modern Art and will travel to Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art and Mexico City’s Museo Jumex later this year. Click here for more information.