MOCA REVIEW: ‘Under the Big Black Sun’ looks at California art in the 1970s

LOS ANGELES — The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles offers one of the finest exhibits in the mega Pacific Standard Time initiative that has swept the museums of southern California like a tempest. Looking at Californian art from 1974 to 1981, “Under the Big Black Sun” takes a holistic approach to the unique time period when art flourished and boundaries were non-existent. Rather than focusing on one particular trend or artist, the exhibit features anything and everything, with very little judgment, discrimination or comment on how these varied parts connect together.

In some ways, the exhibit, which runs through Feb. 13 at the MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary space, is unfocused and still waiting for subtext. However, after viewing the variety of art objects on display, such a feeling is probably appropriate. The Los Angeles art scene in the 1970s was scattered and filled to the brim with experimentation and daring visual displays that often exploded preconceived notions. It proved important; however, the art is difficult to categorize and thus pigeonhole.

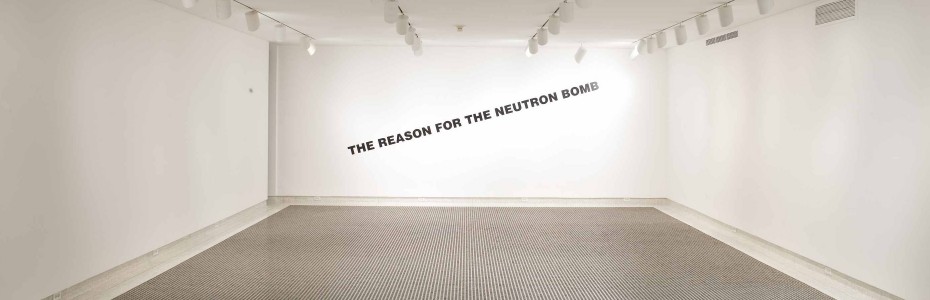

As the exhibit’s title suggests, everything “under the big black sun” is included. From Chris Burden’s moving display of 50,000 nickels and 50,000 matchsticks (“The Reason for the Neutron Bomb”) to Edward Ruscha’s cleverly simplistic “The Back of Hollywood,” the exhibit is one of acceptance and vibrancy, as if “more is better” and “odd is cool.”

Human sexuality is a common thread among many of the pieces, as is presidential politics. John F. Kennedy, Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush are given front-and-center locations. Eleanor Antin’s 1977 video and installation looks at the story of a hijacked plane, while Jack Goldstein uses the iconic lion of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as his inspiration for a video that constantly loops back and forth.

Anthony Hernandez’ photographs of a forgotten Los Angeles evoke a feeling of depression and violence, while Suzanne Lacy’s “Three Weeks in May” draws attention to rape prevention. While some things in “Under the Big Black Sun” are bright and colorful, representing the endless possibility of artistic expression, many of the objects are almost funereal in nature, as if the artists clearly understood the 1960s were dead and the conservatism of the 1980s was on the horizon.

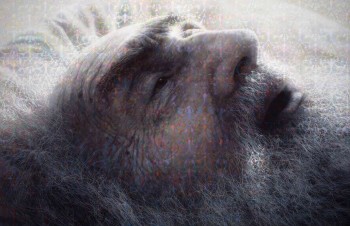

Then there are objects and photographs that stand out for their uniqueness and refusal to connect to the larger theme. Stephen J. Kaltenbach’s “Portrait of My Father” is one of the best pieces, depicting a personal moment of a man contemplating his final years. Superimposed over the man’s skin are little cosmic shapes that look like chromosomes in a rainbow.

Paul McCarthy’s Sailor Meat video is a graphic presentation of the artist dressed in drag and engaging in aggressive sexual behavior with different food items. It’s the definition of absurd and thankfully has its own dark room away from the other objects (for some fun people viewing, check out the reaction of passersby when they first experience McCarthy’s video; their looks are more interesting than the piece itself).

There’s also exclusive concert footage of several punk bands that gained notoriety during the era. It’s a welcome diversion to take a break, sit down and catch a performance of The Dead Kennedys and The Avengers.

Although it’s difficult to pinpoint connections among the artists (besides similar time periods and similar city), there are some loose themes. For one, simplifying what one initially perceives as complex can be seen in many pieces, including “All the Pants I Had Except the Ones I Was Wearing” by Ilene Segalove and Hal Fischer’s photographic diagrams on how to detect sexual cues.

Among them all, Ruscha’s “The Back of Hollywood” is the most effective, telling so much with so little. The painting shows a back view of the famous Hollywood sign. Most Angelenos should know that such a view is impossible, but Ruscha uses a fading sun and vivid reds to show that the land of the sun is not always sunny. There’s a whole world behind the façade.

“Under the Big Black Sun” is a wealth of artistic ebullience and dystopia that fills the Geffen Contemporary’s voluminous space in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. To call it a snapshot of southern California art misses the point. It’s much more a segmentation of a time period, a catch-all basin that doesn’t require an invitation. The only thing not allowed is subtlety.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

-

Under the Big Black Sun continues at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Geffen Contemporary through Feb. 13. The museum is located at 152 North Central Ave. in Los Angeles.

-

Click here for more information.