INTERVIEW: Sachiyo Takahashi’s ‘Sheep #1’ to play Japan Society

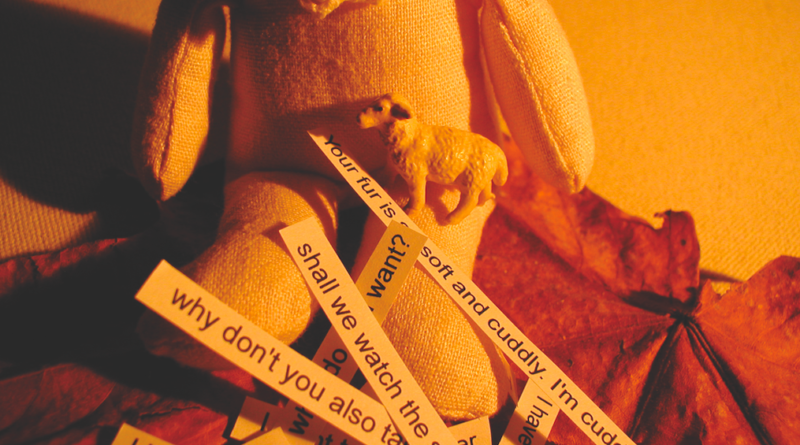

Photo: Sheep #1, created and performed by Sachiyo Takahashi, will play Japan Society. Photo courtesy of Nekaa Lab / Provided by press rep with permission.

Japan Society in New York City will soon play host to the new show Sheep #1, created by and featuring Sachiyo Takahashi. The work consists of storytelling, object theater and live music, with both an intimate performance and projections. The unique evening is actually inspired by the writings of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of The Little Prince, and follows a sheep who is searching for the meaning of life, according to press notes.

In the work, Takahashi uses a technique known as “Microscopic Live Cinema-Theatre,” which finds the performer manipulating tiny figurines that are magnified onto a large screen with a video camera. Performances will take place at Japan Society Nov. 4-7, with two unique programs being performed over four nights — one performance has Takahashi accompanied by a pianist, and the other features a bassist.

Recently Hollywood Soapbox exchanged emails with Takahashi about Sheep #1. According to her biography, she explores the border between narrative and abstraction to generate fables for the subconscious, all done in a minimalist manner. Her work has been seen at Prague Quadrennial, St. Ann’s Warehouse, La MaMa, The Tank and HERE. Questions and answers have been slightly edited for style.

How would you describe Microscopic Live Cinema-Theatre to someone new to the art form?

I use simple technologies such as consumer-grade video cameras and a projector in this art form. Those serve as my magnifier. I manipulate small objects on the tabletop in front of the audience. The audience sees my live manipulation and resulting visuals at the same time. I use manual visual effects — e.g., close-ups, focus, handmade optical filters and lenses to create a dream-like experience enhanced through the combination of cinematic presentation and live operation. Sound is also an essential component of this art form. During the creation, I compose visual and sound elements simultaneously to achieve synergies between them. I would say Microscopic Live Cinema-Theatre is like visible music or poetry in motion.

When were you first introduced to the writings of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry?

When I was doing an internship at a contemporary theatre company in Belgium in my 20s, I ended up in a show where everybody had to play a famous historical or imaginary icon whom you look alike. I couldn’t find any such figure who resembled me. Then, somehow I came across The Little Prince. I was quite an alien in my new life in Europe at that time. Everything seemed strange, and I was asking weird questions all the time as the Prince did. So I became a Little Prince on stage and read Saint-Exupéry’s writings from the inside. I immediately related myself to his way of looking at the world. The way he looks at the world from above: a viewpoint of a pilot, a bird, an astronaut, an alien. It was like he gave the words to the feeling that I always had, but never I could describe. Finally, I realized that I had always observed humanity from above as Antoine did since my childhood.

Did you immediately envision a theatrical work when considering Saint-Exupéry’s words, or did it take time to see how the adaptation might work on the stage?

Sheep #1 is not the adaptation of the work of Saint-Exupéry. It started from a sheep — I had a tiny sheep figurine (who is now a member of Nekaa Lab and the lead for this show) I found in Belgium. The sheep followed me while I relocated from Europe to North America. One day, I thought I would make a story of a journey of this sheep. Since my sheep is tiny, I would magnify it. Thus, Sheep #1, the first repertoires of my Microscopic Live Cinema-Theatre, was born. Of course, sheep is an indispensable element in The Little Prince, and inspiration from Saint-Exupéry was always present.

I ended up using Saint-Exupéry’s texts in this piece just because I felt it was appropriate. Although this work is not a direct interpretation of any of his works, it reflects his philosophies in life.

What’s the most challenging part of performing a piece like this?

I prepare the visual and audio elements beforehand, rather meticulously. But for the day of the performance, I need to be ready to let it go. Since I work with live musicians (Program A with pianist Emile Blondel and Program B with bass guitarist Kato Hideki), each performance has a different energy. Audiences become a part of the piece as well. Some of the elements I use on stage behave differently each time. I feel I am always on the thin line between controllable and non-controllable. I know, though, that the best way is to listen to the moment and respond to unpredictable and coincidences. It is a scary feeling to be fully open to the moment. But if I want to repeat the same “perfect” thing, I would better film the show to make an animation. I believe in liveness, so I am ready to take a risk.

Would you describe SHEEP #1 as minimalist in nature? Does the minimalism make the piece more accessible?

I consider Sheep #1 is an exploration of minimalist or abstract storytelling. Props are dead simple. There are no spoken words. Texts appear as “subtitles” written in small papers, but they are sparse. The story, if any, is quite simple but sensual.

Sheep #1 does not tell you a complete, intricate story. Instead, it creates a space for the audience to follow their own. It serves as a mirror, a safe space to halt and feel, as the performance slows down the sense of time through the language of magnification.

I am not sure if the minimalist nature of the piece makes this work more accessible. I would rather say the simplicity of this work makes it possible for the audience to visit the place where otherwise not accessible. Maybe I am influenced by Japanese traditional art forms. When I see the space, I do not want to fill it all. I like to leave the emptiness for resonance.

When did you first fall in love with stories and storytelling?

I always loved listening to the folk stories that my grandma would tell from time to time. She would repeat the same stories in slight variations each time. It was amazing that I loved listening to the same narrative million times even though I already knew the plot. That was the first encounter with the power of storytelling. My real fascination for storytelling, though, came much later when I discovered Japanese traditional storytelling forms. The interdisciplinary nature of Noh theatre and Bunraku puppet theatre, for example, is quite inspiring from a contemporary perspective. I am also very much in love with Japanese storytelling tradition only through voice, such as Shinnai-bushi that I also perform. Maybe I believe in the words a fox said in The Little Prince: what is essential is invisible to the eye. Perhaps that is why I am always leaning towards listening and trying to catch something invisible and indescribable through my work of art.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Sheep #1, created and performed by Sachiyo Takahashi, will play Japan Society Nov. 4-7. Click here for more information and tickets.