INTERVIEW: Photographer Jay Maisel, in his own words

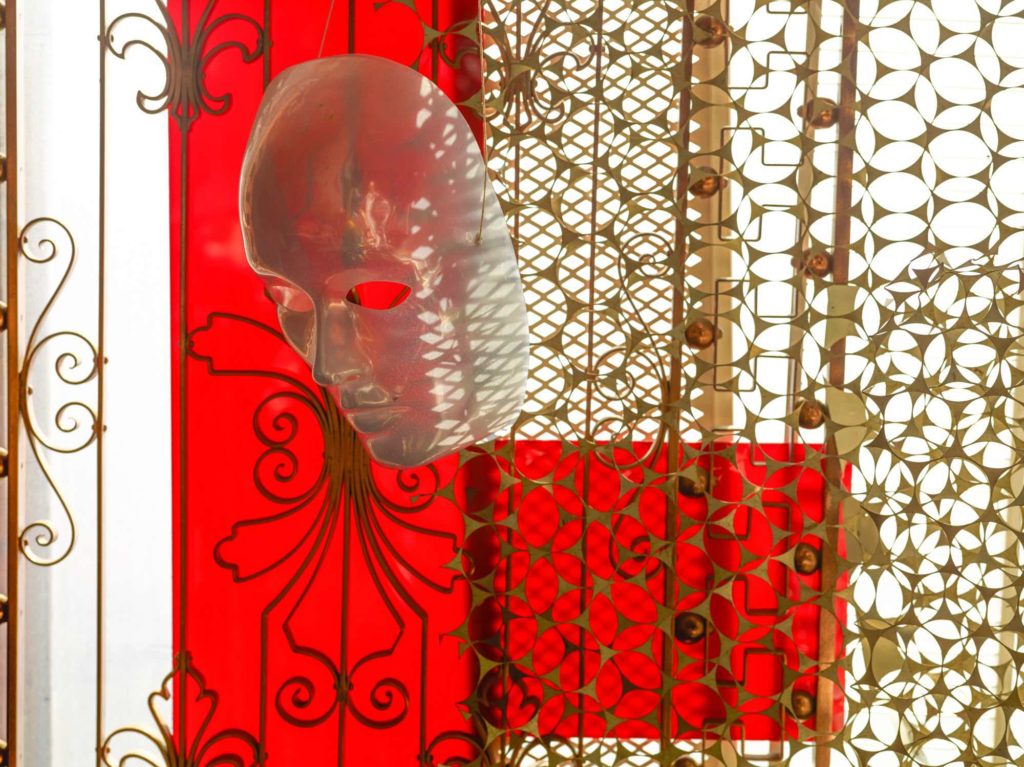

Photo: Jay Maisel has collected many objects over the years; they inspire him in his photographic work. Photo courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories / Provided by Film Forum press site with permission.

Throughout his illustrious career, acclaimed photographer Jay Maisel has put new meaning to the term objet d’art.

Viewers of the new Maisel-centered documentary, Jay Myself, soon find out that the photographer has amassed an unbelievably large and intricate collection of objects that inspire him artistically and challenge him to find even more storage space. There are doodads galore, thingamajigs aplenty and whatchamacallits everywhere. Plus, tools, scrap metal, dolls, jars, vases and lighting fixtures.

For years, Maisel kept all of these objects — everything from antique wheelchairs to rusted kitchen utensils — in his six-floor, 72-room house known as The Bank on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He acquired the bank building in 1966 for a steal and lived within its confines — collecting and photographing — for five decades. It’s there that he built a life with his wife and daughter.

But eventually the monthly costs were up near $300,000 per month, so he looked to the real estate market to get a return on his investment. And what a return it turned out to be.

The sale of The Bank at 190 Bowery for a reported $55 million is believed to be the largest private real estate deal in New York City history, and Jay Myself, directed by Stephen Wilkes and now playing New York City’s Film Forum, details Maisel’s multi-month move out of the gargantuan building. He needed to pack up his collection of objects, and each time a new piece was handled, memories (and opportunity) surfaced to the forefront of his memory.

The money was no doubt a windfall, but the emotions were quite high in those final few weeks, when Maisel reluctantly closed this chapter on his life in Manhattan.

Today, Maisel lives with his family in Brooklyn, and he’s still finding artistic inspiration from the many objects he has collected over the years.

More and more appreciators are learning of his legacy and finding his photographs, which are unique and unparalleled in their breadth and depth. Some of his career highlights, plucked from his official biography: the cover image of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue album, the best-selling jazz album of all time; the first two covers of New York magazine; five Sports Illustrated swimsuit covers; and collections of pictures on a wide array of subjects, everything from Jerusalem to New York City to Hong Kong to Somalia.

Maisel continues to take photographs, though not on the same level he did throughout his years in The Bank. Today, in his late 80s, he likes to look back at the old slides and remember the assignments over the years.

And he has stories to tell.

In a recent phone interview, Maisel offered a glimpse into what it was like to live and work in The Bank, his thoughts on Stephen Wilkes’ Jay Myself, the triumphs and challenges of his photographic career, and his views on a changing Manhattan. Answers have been edited and arranged for style purposes.

Here is Jay Maisel, in his own words.

THE FILM

On whether he was reluctant to let Wilkes film him …

I did it, but I bitterly complained. Have you seen the movie? Did you notice that I’m a grumpy, old man? And I was grumpy because I had a lot on my mind with the move, and Stephen was an extra, added distraction. And at that time, I didn’t have enough prescience to understand that he really was making a very good movie. I had never thought he could make the movie he made because I didn’t think there was anything in there. I was just too close to it to realize the potential. …

I’ve been in constant contact with this guy over the years, and he had told me if you ever get rid of The Bank, you’ve got to let me photograph it.

‘Yeah, yeah, yeah.’

So when I told him I was getting rid of it, he said, ‘OK, now you’ve got to let me in.’

‘My hands are full, man. I don’t want to deal with you.’

But he’s very persuasive, and he did a wonderful thing.

On what his family thought of the film project …

My wife said to me, ‘Listen, you know Stephen. It’s not going to be just Stephen. It’s going to be a crew, and sooner or later, there’s going to be drones and a lift truck.’ And she was absolutely right.

THE OBJECTS

On where the objects are now after he sold The Bank …

They went into storage for about four years, and now I have them back. And I’m probably going to do a book about them.

On the inspiration he draws from the objects …

I just look at them and say, ‘I want it,’ whether it’s a bunch of rocks or whether it’s something expensive that I can’t afford or whether it’s something in nature that I can’t move. It’s something that moves me. It’s an emotional thing. It’s not intellectual at all. It’s a gut feeling.

On keeping track of all the objects …

There are many, many, many, many things I’ve never photographed, and some things that I’ve photographed only in passing and other things that I’ve spent a lot of time on. So it depends on the thing. …

I never remember where the hell I got it. A lot of it is picked up on the street. A very good friend of mine took a picture of me standing inside a dumpster, and he sent it to me. And I said, OK, big deal, but then the title on the back was, ‘I love a man who knows where he stands.’

On the emotion he attaches to each object …

Everything exists on an emotional level. This is not an intellectual, analytical person you’re talking to. I exist on a very emotional level in regards to the objects, in regards to The Bank — my wife even more so. She finds it very hard to go back and look at The Bank. She’s very upset about it.

THE BANK

On his collection of filing cabinets …

Most of the time you’re constrained by spatial limits, and when I got The Bank, it was like 72 fucking rooms. I could do anything I wanted. The big problem was that I needed something to put things in, and at that time, in 1966, you could buy all kinds of file cabinets very reasonable because things were reasonable at that time. So I bought a lot of files. I don’t know if it’s mentioned in the movie, but I’m also kind of a filing cabinet freak. …

Now that I’m living in a different place, one rule in my house, not in the place that I have all the storage stuff, not in the studio, but in my house, I’m not allowed to have filing cabinets above the main floor.

On combining the personal with the professional …

I’ve always lived above the store. It’s always been my habit to live where I work if I possibly can. So even before I had The Bank, I was collecting some stuff, but The Bank just gave me carte blanche.

I don’t know if you want to write these things, but I once had 65 wheelchairs in there. And the wheelchairs had come from a group of young kids who had taken them from Welfare Island in New York, and they were beautiful. They were all oak, and they were all old and antique. And that was because everybody would come to me when I first got The Bank, and they’d say, ‘Listen, we’ve got this stuff, can we store it with you?’ And I let them do it until I realized I was now becoming an unpaid storage house. Finally we had to get rid of everything.

On the sale of The Bank in 1966 …

I thought they were insane to sell it. I thought, my God, in the middle of Manhattan, and they’re giving this thing up. Are they crazy? But at the time, I found out years later, at the time, to the local real estate people, I was a joke to them because I bought this white elephant that I’d never be able to fix up, and I’d never be able to get people to stay there. It was a joke in the neighborhood among all the real estate people. …

Basically I did not have a single person that I knew who encouraged me in my endeavors in this thing except the agent who got me the building, the broker, because everybody looked at me and said, ‘Are you out of your fucking mind? You can’t handle that kind of thing.’ … I didn’t think I could handle it. He said, ‘No, you can afford it,’ and he convinced me I could. He was wrong, but I scraped through. …

I felt I was sitting on a great investment the day after I got it. I just thought how did they let this thing get away so cheap, but I didn’t dream it would be worth what it was worth. That floored me.

On his selling of The Bank in 2015 …

The guy who bought it pretty much respected it and did a very, very good job on it. There were a couple of rooms that he screwed up, but I think that was because it had to be screwed up. And I don’t know about that, but mostly he did what he had to do in a very professional and caring way. … They have two modern elevators, but he took the [old] elevator apart and reassembled it on the second floor behind the glass wall.

On what he misses about the building …

I love the view from the rooftop and the view from The Bank. I miss that tremendously because that was a really rich source of information and pleasure. I mean, I could stand in The Bank for days and shoot for days and never go out. I had the best view in New York, and I never took it for granted. I always knew that I had a great place. It was never like, oh, gee, now that I don’t have it I appreciate it. I appreciated it every moment that I had it.

On the gentrification in the area …

When I left it wasn’t that gentrified. It’s accelerated greatly since I left. Maybe it got better because I left. While I was there, I saw it get a little bit normalized, not gentrified, because when I came there it was awful. There was literally two places to eat within a 20-block area, and there was nothing. There was manufacturing, but it changed. Everything changes, and the minute you get artists in the neighborhood it changes that much faster because they make the neighborhood more attractive, and then they have to move because the rents get too high. …

On the graffiti that lined the exterior of the first floor …

I alternately loved it and hated it. Do you know who Keith Haring is? OK, so, Keith used to do graffiti on the building. Unfortunately he used to do graffiti in chalk. And so the first rain would come, and it would be gone. … He was wonderful, but we didn’t have any idea who Keith Haring was. I said, ‘If you ever see this guy, tell him to use paint. He’s doing beautiful stuff.’

I resented a great deal of it. I liked a great deal of it. What really pissed me off is when they did it on the windows, so that it would block my light. And then they started doing it on the second floor with pumps and everything. It got to be a pain in the ass, but some of it was good. A lot of it was just showing off their tag.

On whether he would ever move back …

I don’t know if that would be a good move because physically it would still be difficult to function in The Bank. I don’t know if I can explain, but, for instance, I used to have to climb up a ladder to get into bed. There were no restrooms on the main floor. I would have had to function a lot differently than I did because I was always climbing stairs, and now climbing stairs is out of the question. It probably would have been a bad move to stay there, but I probably would have done it because you never think how bad it’s going to get.

THE CAREER

On his early days as a photographer …

When I started in the business I was delighted to get any kind of work. … The advertising business in the past had some absolutely marvelous assignments. I mean, Pete Turner was sent to Africa for six months. I was sent to Africa to go to six different countries and do anything I wanted to do. I had an assignment to shoot off-shore oil rigs anywhere I wanted to. There was just wonderful opportunities. For instance, I had two weeks in Iran, shooting Iran. It was an amazing experience, and the fact that it was commercial didn’t matter because I would have done that for nothing. And that’s the kind of assignment I want, one that I would do for nothing if I could.

On why he left commercial photography in the 1990s …

Around ’95 it got very lousy. The terms and conditions of employment had gotten really terrible. It seems to me like it wasn’t fun anymore. Whereas in the past they would send me to Iran or Africa or any of these places and shoot whatever you want, it’s an area of investigation that we want you to do, now it was, ‘We have a layout. We want you to follow that layout.’ Well, I’m not following your layout. I’m not interested in it. That’s the difference. I’m certainly not interested in copying somebody else’s work, so I got out of it. …

It was a snowball effect, but there was one particular time that I had photographed something.

And the guy said, ‘You should have the fishing pole on the left.’

I said, ‘No, it works better on the right.’

‘But it was on the left in the layout.’

I said, ‘I don’t give a fuck about the layout.’

He said, ‘You don’t understand. It’s gone through all kinds of committees for approval. It’s got to be the way it is in the layout.’

I said, ‘No, I’m not going to do it. It’s a bad photograph. We don’t care if it’s in the layout.’

I even got to the point where I said, ‘Listen, why don’t you just send me out to shoot whatever I want, and we’ll take the best pictures. And then you make the layout from the pictures. They’ll never know.’

On photographing for Sports Illustrated …

They were great, and I worked with the same woman all the time who started it, Julie Campbell. And we had a wonderful relationship. We’d scream and argue and loved each other very much, and the women were fantastic.

When you hear the word supermodel it brings up ideas of a certain snobbery and privilege, but the real supermodels, the ones I worked with, people like Cheryl Tiegs and … Elle Macpherson from Australia, they were amazing. They could turn on and off like an electric light. They could give you things that you didn’t even know you wanted, but they gave it to you. It was a lot of fun.

It was also like getting up at 4 a.m. and quitting at 9 p.m. and hoping the girls could get up early in the morning and get made up and going out on boats, and the thing that nobody talks about is that over the years an amazing amount of equipment was lost over the sides of boats. Or in my case, the first day of one of the shoots I stepped on a sea urchin and lost three cameras. Thank God I had brought six along with me.

On his other high-profile assignments …

I shot a lot for myself, and people knew I had a lot of stuff. And they would call me for stock pictures. That business was a very big part of my income, and then it turned to crap because the value of stock picture had degraded greatly because so many people selling it cheap. …

I used to go to a lot of clubs to photograph jazz, and I photographed great musicians. To me, it was like the biggest treat in the world because you got to listen to these wonderful people and got to photograph them, too.

On his image used for the Miles Davis album …

That was not an assignment. That was another thing where they took it out of my file. I had already shot it, and somebody with Columbia called me. ‘We’re looking for pictures of Miles Davis,’ and that’s how they got the shot. …

At that time, I was a young photographer. I was taking pictures. Miles Davis was one of many great guys that I photographed. There was nothing historic about it at all. It was just another thing that I shot that somebody wanted. It happened to become the greatest selling jazz album ever, I don’t think because of my picture, but because of him.

On the competitive nature of commercial photography …

I don’t know if it’s healthy, but it depends how you do it. If you do it by undercutting other guys’ prices or giving away your rights, then you’re a terrible person. If you do it by being better than other people and if you don’t see yourself in competition with people but you see yourself as allied with them because … basically everybody’s triumphs are yours. Everybody that succeeds in something enriched you also.

Ayn Rand once said, and I don’t quote Ayn Rand on anything in the world except this one remark, she said, the difference between a first rater and a second rater is the second rater hates to see anybody better than he is. And the first rater welcomes that because he knows he has an audience now and somebody he can learn from.

On working in Jerusalem in 1974 …

It was a bitch. It was a bitch. It was six weeks long, and what happened, they said they wanted me to go there for four days and shoot. And then they would build a direct mail thing out of the four days, and if they got a big enough response, then I’d go back. And so it got a very good response. I went back for about six weeks, and it was in winter. And it was cold, and it was depressing.

The food was lousy, and the first shot I took of a Druze cop, the very first photograph, he jumped up and started screaming at me that I was trying to make him look bad. Actually what was happening was he was reading a newspaper. I didn’t know if he was supposed to be working, but he was reading a newspaper in the street. It’s incredible.

THE ART

On the different equipment he has used …

I devolved. I use a lot less equipment. When I was working I felt it was my obligation to the client to have every possible piece of equipment I could have, and I carried it all. Sometimes I had to have an assistant. I was carrying from a 15mm to a 1,000mm, so little lens to huge lenses. Then when I stopped doing commercial work, I didn’t owe anything to anybody. I could shoot whatever I want, so I tried to go out with one lens and one camera. And I picked a zoom lens, and I didn’t carry a lot of stuff with me.

On finding the best photograph …

I think it’s not the eye. I think it’s more the concept, the brain. I find that I shoot a lot more on people than I used to. I shot a lot of people in the past, but I’m shooting a lot more on people after I quit doing commercial work. And, I used to shoot a lot of nature. I’m not at all interested in nature now, so you do evolve. I don’t know whether you get better or worse, but if you listen to what’s going on inside of your head, which is a very crowded place, if you listen to that, you find things that you may not have been aware of that you are now interested in. And you find other things just don’t interest you anymore. You go through periods. …

I can only speak for myself. I don’t know how it is for other people, but I think that if one has curiosity, that’s the main thing you need to be a photographer. If you have that, you’ll find your way.

By the way, I once interviewed an actress, and I said, ‘What do you think the most important thing for an actress to have?’ And she said, ‘Curiosity,’ and that blew me away because that’s crossing different fields totally.

On his early painting …

In the film, it talks about the fact that I was a painter, and I got my BFA in painting. So I was very interested in graphic arts and design and architecture and calligraphy and sculpture. It was a very, very important part of my upbringing. … I don’t do it [anymore], but I think it had a great influence on my work. I’m not doing painting. I’m not doing calligraphy, but all these things are part of me now.

On his decision to leave painting for photography …

I did not plan to be a photographer. I became a photographer because it was so much fun and because I’m kind of the guy that likes instant gratification. I could take a picture and see it that night, see what I’ve gotten. It was very rewarding, but I didn’t really become a serious photographer until I was about 23, at which point I decided I had gotten my degree my painting and decided I didn’t want to paint anymore. I wanted to be a photographer. It was very hard. …

I don’t know if I had the courage to be a painter, even if I was a better painter. I’ve always said, the thing that I say to all my students, is if you’re not your own severest critic, you’re your own worst enemy. So you have to learn not to worry about external validation, but make your own decisions about your work. And I looked at my work and my painting, and I said, ‘You’re just not that good.’ Because the more I worked on a painting, the worse the painting got. Somebody once said, it’s not knowing how to start; it’s knowing how to stop that makes work valuable. You’ve got to know when to quit. I never knew when to quit. I would just keep working until I ruined it.

On working in New York vs. other parts of the world …

In my work, I have access in New York. I’m not worried about anything. I know exactly where to go. If I did something, and I need to do further work on it, I do it.

These [other] places I’ve been to, I’ve been there for a very short time, but that’s both a curse and a blessing because everything is new. You’re going to miss an awful lot of stuff, and that’s the nature of life. You’re always going to miss stuff, but whatever I’m seeing is fresh and new to me, very exciting. When you photograph in a new place, it’s like the life becomes kaleidoscopic, and it starts coming toward you at such an incredible speed and diversity. And you’re just trying desperately to catch a piece of it.

When you’re photographing your own hometown, you know exactly what’s going on. It still has a kaleidoscopic quality when it’s good, but basically you’re in charge. And the danger in being in charge is that you may not allow yourself to be filled with the subject. You may have preconception, and it’s much better to go out empty and be filled by the subject. …

I don’t like to find out too much about a place before I go because then I’m preconceiving again. I like to get hit with what is there, and I want that first impression because you can never get a first impression on the second time around.

THE FUTURE

On his continued photography career …

I’m physically unable to because it’s difficult for me. I can stand, and I can walk. But I can’t photograph and stand in one place because I’ll fall over because I don’t have the balance I need, but I still photograph on occasion, but not the way I used to. I still carry a camera with me, but I’m using the cellphone camera, which has improved to a degree that’s unbelievable compared to what it used to be. So I use that because it’s not a heavy thing, but otherwise I’m not carrying my camera around.

I will shoot where I can sit or where I can stand or lean against something, but it’s very difficult to shoot the way I used to because my shooting was very physical. I mean, I was climbing on things. I was crawling on the floor. It wasn’t [just] shooting from the heights of my eyeballs, and now I can’t do that anymore. …

I always, always, always, always had the camera. That’s why this is a difficult time for me because I can’t always, always have the camera now. The cellphone has filled in a gap, but it’s still not the same.

On looking back at his slides …

I always look back. One of the things that I’ve done in the last three or four years, where I can’t move around as much as I’d like to, is I’ve taken this time … and I can work on my files. I’ve been going through all my pictures. I know a few other guys who have made it to my age, and they’re doing the same thing because it’s a real rare privilege to be able to look over your pictures because you never get a chance to while you’re working. And most guys work until they die. This last three or four years, I’ve been going through all the stuff I’ve done in all the different countries, and I’ve been putting them on my website.

On the power of teaching the art form to others …

To me, it’s self-evident. You teach because you want to impart something to people. It’s also why you paint and photograph. You want to change somebody’s view of life, and I’ve been very fortunate to have had students that really appreciated what I was about. People say, ‘Well, it’s tough to be a teacher.’ I said, ‘No, it’s tough to be a teacher of students who don’t want to learn.’ But everybody I’ve ever taught wanted to come to listen to me, so it’s relatively easy.

On his legacy …

I don’t mean to say this in a modest way, but I don’t know what my legacy will be. I’ll probably be a very, very minor figure in photography who was known for making a killing in real estate, and I think the objects are going to overtake my pictures because people seem to be more interested in the objects. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I know I have amazing photographs, but that’s just my opinion. It doesn’t mean anybody else in 20 or 30 years is going to think they’re so fucking amazing. I’m looking at them now, and I say, ‘They’re good. They’re good.’

I’ll stand by them.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Jay Myself, featuring Jay Maisel and directed by Stephen Wilkes, is now playing New York City’s Film Forum. Click here for more information and tickets.

Updated: 08/19