INTERVIEW: Martín Santangelo combines flamenco, Greek tragedy in ‘Antigona’

Noche Flamenca, formed by the husband-wife team of Martín Santangelo and Soledad Barrio more than 20 years ago, has built a worldwide reputation for its simultaneous cherishing of classic flamenco and determined goal of taking the art form in new directions. That dichotomous mission is on full display in the company’s latest work, a flamenco interpretation of Sophocles’ Antigona, which is playing a return engagement at the West Park Presbyterian Church in New York City through Jan. 23.

Santangelo said the original run this past summer was “very good,” but he wanted to give New Yorkers who went away in the warmer months the chance to catch the critically acclaimed show.

CREATING ANTIGONA

The genesis for the 90-minute piece can be found in ancient Greek tragedy and also the drama of the Spanish courts. The artistic director of Noche Flamenca said one inspiration for telling this tale in 2015 is because of Baltasar Garzón, the “human rights judge” who drew much attention in his home country when he opened investigations into the atrocities committed by the Francisco Franco regime.

Sophocles’ drama depicts two brothers, both sons of Oedipus, who kill each other. Their sister, Antigona, wants to bury both of them and have proper funerals. However, the dictator, Antigona’s uncle, labels one sibling as the good brother and the other as the bad brother.

“And she’s not interested in politics,” Santangelo said of the central character. “She’s interested in respecting her family and humanity, so the big conflict in the play [is] do we run our lives through manmade laws or nature’s laws, which includes love of family, respect of family.”

Santangelo, who is credited with adapting and directing the piece, said the unique aspect of the show is the narrative, which breaks from the usual structure of a classic flamenco performance. “From the get-go, the most important thing from the beginning even to now is telling the story,” he said. “If the story is not clear, it doesn’t matter how good or bad the flamenco is. … No matter what, I made a rule for myself: Tell the story.”

At first, Santangelo worked on adapting Sophocles’ words into “singable” lyrics that would work for his flamenco performers. That process took a couple of years. “I had no idea how difficult that was,” he said. “That was a big chunk of work. The choreography came well afterward. It was the last thing we did, and so we had a very, very specific and complex roadmap of the song structure of music and song that we would lay the choreography on to.”

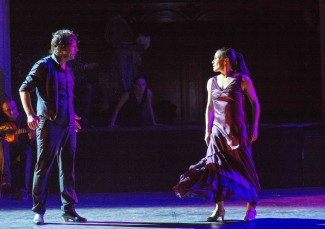

Santangelo’s wife, Barrio, who is the main dancer in Noche Flamenca, plays Antigona. She is also credited with the choreography for the show. New York audiences have seen her spirited dancing for years in a variety of venues. Barrio and the company have been frequent presences on the stages of Joe’s Pub, the Joyce Theatre, Cherry Lane Theatre and now West Park Presbyterian Church.

The artistic director said he was a bit apprehensive at first when attempting to adapt the Greek tragedy; however, the piece eventually won him over.

“Little by little it seemed like a logical choice because the flamenco has one part that is … a desperate, archaic scream for justice, whether it be personal justice, or society’s justice or just plain old conflicts in life looking for resolution of conflicts,” he said. “And it’s a great vehicle to express Greek tragedy. … At first, I thought, yeah, I’m half-crazy, but then the more I went into it, I thought my God this really … makes sense. You know, Sole always has an internal conflict when she’s dancing. To give her a character like Antigona and put her into a scene where there’s a written conflict, it makes even more sense to see her dance. It made a lot of sense for me.”

Both Greek tragedy and flamenco, which has roots in Spain, emphasize catharsis. Santangelo referenced the ancient festival of Dionysus where the poets attempted to educate the masses by having them undergo an emotional, theatrical journey.

“The same thing occurs in the flamenco,” he said. “People began singing because they were … uprooted. They lost their homes, or because of racist acts, somebody in the family would die. And they would sing … to have a catharsis to be able to wake up the next morning and go on with their lives. So the two things, the cathartic element is built into both of those things. It’s built into flamenco and, of course, Greek tragedy.”

Antigona has undergone several changes from Santangelo’s initial idea to the presentation that audiences will see at the West Park Presbyterian Church.

“I have my plan, but as always, flamenco is a collaborative art form,” he said. “[Noche Flamenca] had to collaborate because I needed them to give me the language of flamenco. We needed to get even more specific about classic flamenco to be able to express certain things, so we spent a tremendous amount of time together, the entire company, scratching our heads trying to figure this out.”

He added, with a laugh: “So, yes, it was collaborative — up to a point.”

When the show first premiered, Santangelo was probably in the shadows “terrified, terrified, terrified.” His nerves had to do with the storytelling aspect of the show. He wanted to make sure the dancers and singers actually brought the original tale to life.

“The first few times that we did it, I had talkbacks, and my first questions were, ‘Do you understand the story? Is there anything that’s not clear?’ And if I got any little remark about this moment they were confused, they didn’t understand the story, then … the next morning I would be back in rehearsal with the entire company.”

CREATING NOCHE FLAMENCA

Noche Flamenca has a dedicated core of musicians and dancers. Among them are dancer Juan Ogalla, guitarist Eugenio Iglesias, guitarist Salva de Maria, percussionist David Rodriguez, singer Manuel Gago, singer Emilio Florido, dancer Marina Elana and musician Hamed Traore.

The idea for Noche Flamenca came to Barrio and Santangelo in 1993, and their original creative decision was mostly one of utility.

“To tell you the truth, the reasons for creating the show was so Sole and I could have time together because we were working with different companies, and we really wanted to just spend time together,” Santangelo said. “So we began working together to unite, and that objective has kind of permeated the entire company that a lot of times it goes beyond just hiring this artist or that artist. A lot of times, the reason the core group has stuck together, it’s almost like a family that we miss each other when we’re not together. We enjoy being together, and we have a very tight-knit community within our group. And it’s become like family. It’s like I have brothers, and sisters, and sons and fathers in the company, which is quite beautiful.”

Since those early days, when Noche Flamenca was simply an idea, the company has grown substantially, in numbers and renown. However, even though the art of dance is fulfilling, the business of dance can be draining. “I want to just keep doing whatever things come to my imagination,” he said. “I don’t want to get into the groove of fulfilling a certain identity or a commercial identity of the company. I try not to think about that.”

He added: “The money is one of the most grueling parts of it because there’s no money in dance, or there’s no money in what I’m doing. And unfortunately when I do have money, I spend it on productions.”

Santangelo seemed destined to interpret flamenco as a career. As a young man, growing up in the West Village of New York City, his parents became friends with a flamenco couple. “And he and his wife lived with us for four years in the West Village in New York City, and the biggest artists would be in my house rehearsing, performing, getting together, getting drunk together,” Santangelo said. “So I had this crazy, wonderful, odd exposure to flamenco in New York with the giants of flamenco.”

From those early days of watching the art form, which melds together dancing, singing and instrumental work, Santangelo has built a career and a life. The future holds much promise. Because of the focus on narrative in Antigona, the artistic director would like to continue the storytelling exploration. He is working on an adaptation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and another project that focuses on the Jewish, Arabic and Catholic roots of flamenco.

“I have tons of projects in my mind,” he said. “It’s just a matter of having time and resources to do them, but, yes, I’m constantly working on the next thing.”

Santangelo is a man caught up in the story.

“Narrative will be part of the future because I realize that … the language of flamenco can express in a very immediate way, in a very unpretentious way, great stories,” he said. “I don’t want to limit myself.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

- Antigona from Noche Flamenca is currently playing the West Park Presbyterian Church at 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan, N.Y. Click here for more information on tickets. The show, adapted and directed by Martín Santangelo, features a cast of singers and dancers, including Soledad Barrio.