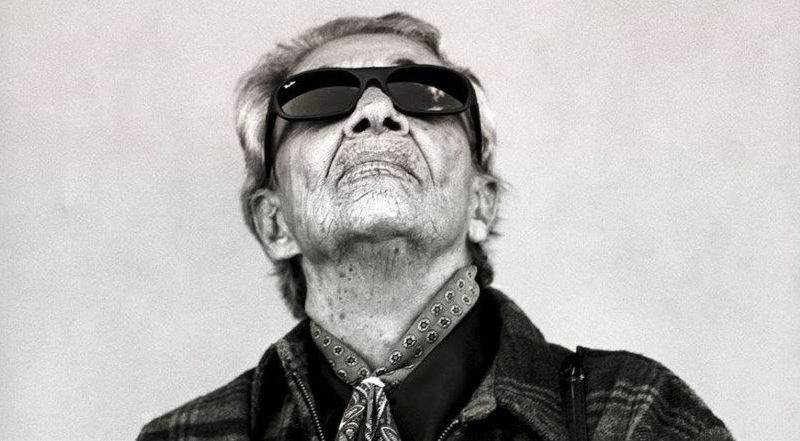

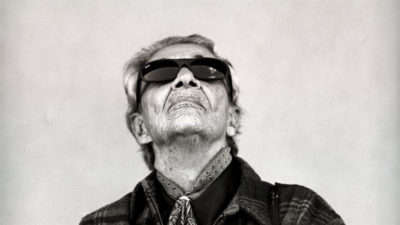

INTERVIEW: Influence of singer Chavela Vargas explored in new doc

Catherine Gund and Daresha Kyi’s new film explores the life and legacy of popular singer Chavela Vargas, a chanteuse from Mexico who left her mark in the music industry and society in general. The film couples archival footage of Vargas, who died a few years ago, and tells her story of being a soul-filled live performer, being a lesbian, being an inspirational presence for her fans and being a one-of-a-kind interpreter of Mexican rancheras.

Vargas was born Isabel Vargas Lizano in Costa Rica in 1919 and eventually landed in the streets of Mexico City in her teenage years. She was a frequent presence as a singer in nightclubs and challenged the norms of the day by dressing in men’s clothes. The documentary’s official website states that Vargas enjoyed cigars, tequila and music. She even lived with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera for some time.

Along the way, Vargas celebrated many personal and professional milestones. She earned a Grammy Award and interpreted many classics, including perhaps her most famous tunes, “La Llorona” and “Paloma Negra.” She is also remembered as a trailblazer for the LGBTQ community.

Recently, Hollywood Soapbox exchanged emails with Gund about her new film. Questions and answers have been slightly edited for style.

What inspired you to make a documentary about Chavela Vargas?

When my best friend died of AIDS in 1990, I fled to Mexico and was introduced to Chavela Vargas’ songs by my new friends who revered her. They saw my video camera, my constant companion, as I captured her concerts in a small cabaret, and they were determined to interview their legend, their icon, their fearless role model.

She invited us to her home in Ahuatepec. The resulting footage sat in a box in the back of my closet for decades. Although Chavela was already 71 when we interviewed her, I realize now that she had to finish writing her story so that this film could tell it. She went on to gain international superstar diva status and performed for another 20 years. Her music moved me in 1991, and her music moves me today. But her soul and her choices in life are what truly rattle my core, reminding me constantly to live my one life as honestly and fiercely as I possibly can.

How would you define her musical sound?

Chavela’s voice and her singular magic transcends space and time, wrenching our souls, tapping into our deepest grief and our most radiant immortalizing love. She carries her grief deep in her soul, tapping into it like fuel when she sings. As she says, ‘I offer my pain to people who come to see me. And it’s beautiful.’

How do you strike the balance between personal and professional in the documentary?

Art is thoroughly personal — for those who make it and for those who seek its singular rewards. For me to understand why Chavela’s music invariably brings me to tears, I needed to know more about her life, her community, her context, the fashion, the photography, the lovers and friends, the richness of her unique journey. Her music represents itself, but it’s the tendrils of reference and insulation that tear beneath the surface of critical review and ticket sales. The capacity of film to chart a multidimensional, textured adventure into a distinct sound and personality is the force we chose to wrangle.

Chavela Vargas is often considered a trailblazer. What do you feel her story says about gender? Sexuality? The music industry?

Chavela’s journey displays all the pitfalls and promises of an ultimate success. She was the most outside of outsiders, seriously isolated and lonely throughout her childhood and probably all the way up until she became sober at 70 years old. The kind of social pressure that seeks to deny people their fundamental humanity nearly killed her, but she persevered.

She honored queerness, bravery, aging, non binary gender expression, femininity, masculinity, community and compassionate love for herself and others by virtue of staying visible, never hiding who she was, or how she felt and expressed desire.

I know much less about the music industry except that it exists within the confines of mainstream culture, dominated by white men who have no experience and/or little interest in sharing power and vision with others, especially those who are different from them, those who are marginalized, emotionally powerful and artistically gifted with the ability to communicate. Chavela’s very being called into question how fairness and justice had been (often intentionally) withheld from her. In the end, thankfully, she carried us all along, towards a more nuanced yet furious truth.

When you hear Chavela Vargas’ recordings, what goes through your mind?

I feel love, honestly, and that’s what I try to convey to viewers of the film. I want them to feel like difference is positive, enriching and generative. I want them to believe in themselves and all of those around them. I want them to know that we each have something to contribute. She motivates those of us who discover her to pursue our own desires, to transform ourselves into our most incorruptible, brave and responsive selves. I want viewers to choose Chavela’s songs when they’re picking the soundtrack of their lives because she transcends and creates empathy, and there will only be justice when there is empathy.

Why was it important to include her fans in the film?

Everyone who met Chavela or heard her music seems to be her fan. She was roundly adored notwithstanding her difficult personality, her often unfriendly character, her tendency towards violence or at least hostile discord. We wanted to present a broad sketch of who Chavela was, not just focusing on her enthralling, captivating, enigmatic side.

Her fans felt her music deeply within their own souls. They came back to hear her time after time, to cry with her, passing tissues along the rows in the world’s biggest concert halls. They passed her song down through generations and wordlessly familiarized their children and their children’s children with her genius. How could we leave out that half of her story? She lived for the stage. She wanted to die on stage. She wanted to die singing for people. She created desire in her fans, and in response, we kept her alive — for as long as [we] could.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Chavela is currently playing New York City’s Film Forum. Click here for more information and tickets.