INTERVIEW: Expert offers background on Nat Geo Wild’s ‘Kingdom of the Apes’ special

Seeing the majestic mountain gorillas of Virunga National Park, located along the borders of Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, can be a faraway dream for aspiring conservationists. Seeing the chimpanzees of Tanzania may be another image steeped in exoticism, stuck in the distant wilds of eastern Africa and the pages of Jane Goodall’s primatology research. Catching sight of these threatened species is probably on many bucket lists, but Nat Geo Wild will allow access to both sets of animals beginning Sunday, July 13 at 9 p.m.

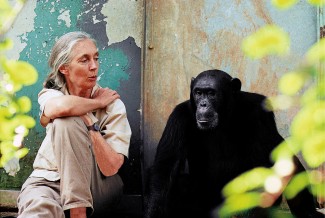

Kingdom of the Apes, a two-part miniseries introduced by Goodall, will premiere on the channel, offering viewers a free passport to amazing footage from these wildly exciting areas and their endlessly interesting habitants. Of course, the underlying atmosphere that pervades the narrative is one filled with dire circumstances. Primates unfortunately are not guarantees for the future; they need protection, for individual species and habitats, in order to survive and thrive in areas with unique obstacles (a recent documentary looks at this issue head on).

The gorilla episode of Kingdom of the Apes focuses on Titus, a “silverback king” who battles to retain his crown. The chimpanzee episode examines sibling rivalry between two animals lovingly coined Freud and Frodo (perhaps one is a deep thinker, the other on a perilous quest).

Primatologist Mireya Mayor knows the apes of eastern Africa well. Her own journey to this “kingdom” began as the daughter of Cuban immigrants and continued along a fascinatingly intricate path: She was a NFL cheerleader for the Miami Dolphins, Rhodes scholar, field scientist and eventual National Geographic correspondent for Ultimate Explorer.

Mayor was on a team with the Wildlife Conservation Society that discovered a group of lowland gorillas in northern Congo, according to Nat Geo. This group was previously unaccounted for, and from the pictures available from the journey, Mayor seems delighted with the discovery. Goodall actually wrote the introduction for Mayor’s book, Pink Boots and a Machete.

In anticipation of Kingdom of the Apes, Hollywood Soapbox exchanged emails with Mayor to find out a little more about primates, the unique quality of wildlife documentaries and her journey to the hearts of so many animals.

For most viewers watching Kingdom of the Apes, seeing these primates in the wild will never happen. Does that make the work of TV producers / conservationists especially important because this may be the only chance of seeing these animals, at least for some audience members?

Only a handful of scientists have seen firsthand these critically endangered animals in their wild habitats. At a time where we may be facing potential extinctions, filmmakers are the unsung heroes that capture these compelling visuals through their hard work, patience and dedication and bring them to audiences worldwide.

The media is an immensely powerful tool and platform for conservationists because it transports viewers to places they may never go, shows them the beauty and depth of animals they may never see and potentially inspires them to care more about our planet.

How did you get interested in studying primates?

As I discuss in my book, Pink Boots and a Machete, I always loved animals as a child but I took a very unconventional path into this field. I was an NFL cheerleader for the Miami Dolphins attending the University of Miami, on a pre-law track. I had to fulfill a science requirement and arbitrarily chose an anthropology class. I began to learn about the incredible primates that were on the verge of extinction and that we knew so very little about and decided I wanted to do something. So I applied for a grant and headed to Guyana in South America, one of the most remote and unexplored places on earth.

There is an ongoing debate on whether researchers should give animals human names (Frodo is mentioned in Kingdom of the Apes) and draw narratives from their behaviors. Some say researchers should not become attached, and others believe empathy/understanding is OK. Where do you fall in this debate?

Animals are named during studies for the simple ability to refer to them. In many instances, it is the locals who name them. In this way, you can refer to the particular individual by name when recording data and behaviors. I happen to also believe that naming them is a powerful tool in conservation, because you do somehow become more “attached” and that care is the very thing that keeps them alive.

Anyone who has spent any amount of time in the field with these animals knows it is impossible not to become emotionally attached to them as individuals.

How do you know a great story in the wild will make for a great story on TV?

A great character, whether animal or human, passion, mystery and beautiful visual imagery make for great TV. People need to connect and feel moved. Kingdom of the Apes has all these things.

You stress “local support” for conservation success. Could you describe how this works and why it’s so vitally important?

Without the help and support of the local people, you cannot have a successful conservation project. The local people are generally poor in areas of rich biodiversity. They need to survive too. By involving them in the project, and improving their livelihoods, you increase your chances of success. Many times animals are hunted or their habitats are destroyed because there are no alternatives for the locals. Animals and humans share these habitats and the only way for them to coexist is when the locals are on board.

I work with Centre ValBio, a Stony Brook University non-profit organization that serves as the perfect example of how a good relationship with the local villagers plays a critical role in effective conservation.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com