INTERVIEW: Enter the world of slime molds with director Tim Grabham

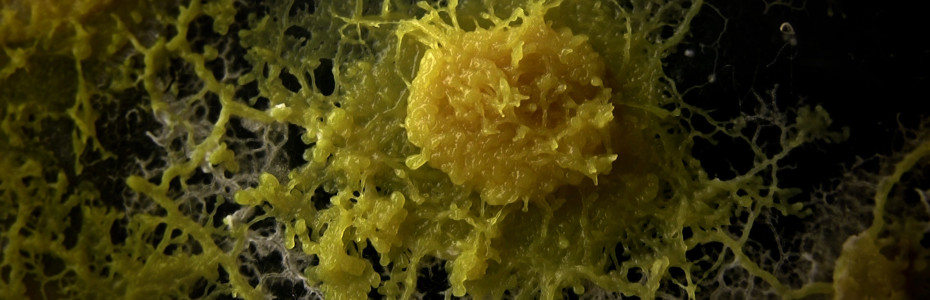

Slime molds are fascinating organisms that almost defy classification. They move at an improbably slow pace, feature electric colors and apparently enjoy carbohydrates. Neither fungi nor animal, slime molds are part science, part science fiction, wholly fascinating. They move but have no brain.

The molds are subject of the new documentary The Creeping Garden, currently playing the Film Forum in New York City. Co-directors Tim Grabham and Jasper Sharp have worked on the movie for quite some time, helping bring these slime molds to life thanks to the atmospheric soundtrack by Jim O’Rourke and a host of artists and researchers who are looking closer at these odd, natural phenomena.

Grabham, who uses the pseudonym iloobia for his animation work, first met Sharp on a previous project that was making its way around the festival circuit.

“We became very good friends,” Grabham said recently during a phone interview. “And he [Sharp] started to introduce me to idea of the slime mold. Over various very strange meetings, he kept telling me all this amazing stuff about what the slime mold was and his research — people making computers, people doing transportation network models with it. And the more he kind of introduced me to it, the more I was just enthralled by this whole thing. And it took us a while to work out exactly how we were going to make this into something that an audience might be able to engage with for a feature-length running time. But it was really just kind of slowly, slowly following the research he was doing, finding it out in the wild and getting our heads around [how] the human contributors could probably augment the story of the slime mold and give it that sort of longevity needed for a long-form piece.”

Those human contributors include artists, researchers and sound experts who use the slime molds and their unique movements to perform experiments and even create art. Audiences will see slime molds working their way through a maze, almost like laboratory mice. The Creeping Garden also features a musical performance made possible by the mold.

“There’s a lot of types of slime molds, and different ones have different sort of rates of motion,” the co-director said. “If you fill up the Petri dish with lots of oat flakes, it tends to be rather lazy and just sits on the food. So it’s also dynamic. So all that sounds a bit cruel. It’s better to sort of deprive it just a little bit of food to make it work for its food to get better sort of time lapses out of it.”

Those time lapses allow audience members to see the movements of the molds sped up and, thus, noticeable. With the naked eye, these organisms look like colorful blobs attached to rotting trees. They definitely look stationary and not mobile. The fact that they move has sometimes caused them to be classified as space oddities, as one news report in the documentary suggests.

“The film is surprisingly lo-fi to be honest,” Grabham said of the technology used in the filming process. “We were on such a thin budget that we had to use all the available cameras and things that we had, and in an ideal world, you would have set up like a really nice sort of camera on a time-lapse mechanism to get this working over like one or two days so you really get the spread of the motion, which is what people had to do. We were running on like very thin budget, so the best I had, the best lens I had, macro lens, was on a tape-based video camera, which had a fantastic macro lens, but only an hour-long capacity for recording. And this felt restrictive, and it felt impossible because most nature doesn’t do very much, non-animal nature I should say, doesn’t do very much in one hour. Slime molds surprised us greatly for being very dynamic within an hour. So when you speed those times up from one hour to like 30 seconds, you see that sensual, undulating motion that most people don’t bother capturing because they capture it for eight hours or 12 hours. So we actually discovered through the restrictions of our camera equipment, we were getting a new view of the behavior and movement of this organism through actually having really quite basic technology, you know just a handy cam with a really great macro lens on it.”

Finding slime mold in the natural world turned out to be quite easy. Grabham said they are bright colored, often featuring pink and yellow shades. Turning over rotting logs helps with the discovery as well. “We just took some walks into the forests,” he said. “You can start to spot them fairly quickly, and once you start to realize where you’re looking, it’s surprising how much they sort of stand out to you.”

The scientific and artistic information is not presented like other documentaries. The directors definitely heighten the oddity of the molds and play with science-fiction genre characteristics.

“I think when we realized that we were kind of on our own in the sense of no real funding and no support from anyone else, we realized that we had absolute creative freedom, which actually for me, and Jasper I think agrees, is one of the greatest currencies you can have as a filmmaker,” Grabham said. “We like our sort of odd 1970s sci-fi films, among others. We looked to films like The Andromeda Strain, Phase IV was another one, a very sort of obscure pseudo-documentary called The Hellstrom Chronicle. These were all quite influential in the sort of tone we wanted, which was real science embedded within something that was a science-fiction narrative. … And we thought, wow, wouldn’t it be cool to make a film that’s a documentary but does look actually like a fiction movie. So whether or not that worked or whether that plays out very well, that’s for the audience to decide. But that definitely from the outset was our ambition. We didn’t want to do a prescribed voiceover-led, TV-star, factual documentary presentation for this because it felt like we were given that rare opportunity to present it in a fun and creative way, which hopefully for the audience is much more surprising and entertaining.”

O’Rourke is responsible for most of the music throughout the film. It’s appropriately creepy and serves as a soundtrack to the unique movements of the molds.

“[O’Rourke] was really into it because he found the subject matter compelling,” the co-director said. “So we sort of sent him clips, rough cuts of different scenes that we were doing. And then we didn’t hear anything from him for months, and months, and months and months. And we were starting to panic, thinking, well, we need an alternative soundtrack because we’re getting toward the sort of deeper edit stage. And without music, this is becoming really challenging. And then with a bit of poking, he suddenly started feeding us huge quantities of textures, soundscapes … borderline music, sound design, and just being very giving as a composer, just saying use this how you need to use it. … We wanted sort of arrhythmic, atonal sounds and textures that left lots of room for the sound design that was being worked on and the dialogue, of course.”

Grabham’s professional background is varied and unconventional. His animation work consists of a motley variety of “weird little short films,” as he put it. His last feature documentary was KanZeOn, about Buddhist philosophy in Japan. “I like to think that immersive experiences for audiences is a better way for them to grasp ideas,” he said. “The last thing you want to do is try and have someone go, ‘This is what Buddhist philosophy is.’ We wanted people to feel it, and that’s very much something that I think is important in a film, is to allow the audience to be immersed, involved very much, deciphering puzzles, getting involved in something that’s not just laid out to them and fully explained. They have to do a little bit of work, which hopefully is an enjoyable experience. The feedback we’ve had from them is that it is.”

His next project, with a working title of The Hibernating Mind, is a documentary about cryogenics. It should be “experiential”and “unconventional.”

From slime molds to philosophy to cryogenics, Grabham enjoys diving deep into stories that beg for closer inspection. He not only depicts his subjects; he lets them tell the story.

“We decided that the behavior and the way the slime mold works and explores its world should be the way that we made the film,” the co-director said. “So as we went and met one person, they gave us some information and a little tip to go and check someone else out. And we would go and explore that sort of person, and then they’d lead us to the next person. … This was probably why it was quite hard for us to get funding because really our pitch was pretty vague, and people don’t really like vague pitches when you’re trying to get money off them. They like to have something fairly concrete. But, no, that was actually a benefit, I think, the sort of sprawling indirect way that the slime mold works became the model for the way we made the film.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

- The Creeping Garden is currently playing the Film Forum in New York City. Click here for more information.