INTERVIEW: Documentarian visits Ricky Leacock in Normandy

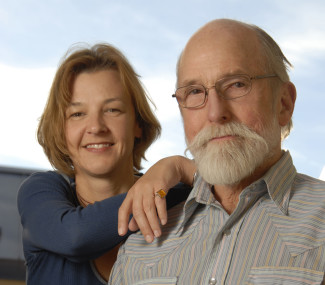

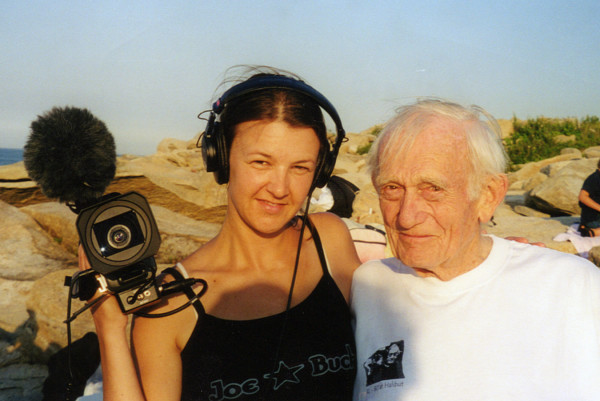

Cinéma vérité may be a household name nowadays (at least in the households of documentary filmmakers), but back when Ricky Leacock, Les Blank and their contemporaries were starting out in film, the style was novel and unpredictable. The directness of the reality on screen seemed both comforting and aggressive, a testimony of testimonies. In the new film How to Smell a Rose: A Visit With Ricky Leacock in Normandy, Blank and co-director Gina Leibrecht follow Leacock as he enjoys life, cooks exceptional meals and talks about his influential work.

The film, which recently premiered at New York City’s Film Forum, stands as an important document about a late, great documentarian. The new film is coupled with Leacock’s A Happy Mother’s Day at the Film Forum.

“I met Les Blank probably in 1998, and he had been talking about Ricky Leacock,” Leibrecht said recently during a phone interview. “I think he had already filmed some footage of Ricky Leacock that he showed me, and around 2000 I suggested we go back and film Ricky some more. So Les agreed, and I brought my camera. And we spent a few days with him in Normandy and filmed him, and then I started editing the film. And all these years went by, and I finished the film just last summer.”

Leibrecht, who worked with Blank on All in This Tea, said that when she met Leacock, he enjoyed being alive and that his positivity was infectious.

“He was extremely happy to be where he was in life,” he said. “He says it at the end of the movie. He says, ‘This is the most exciting time of my life as a filmmaker,’ and I think that he exuded that, that kind of happiness. He an opinionated person, but … he was very likable, very charismatic.”

Leibrecht said the project was able to work because Leacock trusted Blank. The filmmaking style was also fairly casual, with the directors following their subject around, sitting at his table and enjoying life. “And every once in a while we pulled out the camera,” she said. “We didn’t film him all day every day, just when the conversation got juicy and when he was cooking obviously. … He had some opinions about the way that we did things because he would have done them differently. For example, we put a wireless lavaliere on him, and he was really opposed to that. He said I would never do that to my subject, but we insisted on doing it because the sound is infinitely better if you have a lavaliere on someone. And he thought our camera was too big and heavy. He let us know that he didn’t completely approve of the way we were doing things, but then he let us alone because it wasn’t his film.”

When Leibrecht first met Leacock, she had a bit of a learning curve. She had heard of his contemporaries, including D.A. Pennebaker and Al Maysles, but Leacock’s work wasn’t known to her.

“I even went to film school, and I hadn’t heard of him,” she said. “I basically went on this trip not knowing very much about him at all. I went in pretty blind, and it wasn’t until after the trip that I really got to know who he was. I started really doing his research, and I was impressed by the fact that I didn’t know him because his work was so influential. But he was a little bit in the shadows because he ended up at MIT and taking a different path from the other guys that he had worked with.”

The resulting film is an “educational” movie that can help young filmmakers, perhaps on their techniques, style and choice of subjects. “I definitely want this to be an educational film, but at the same time just because it’s educational it doesn’t have to be dry,” she said. “It’s not a comprehensive kind of film in that way about the history. It’s more of a portal into that time, into that moment in history, and it’s also a way of looking at history in a kind of a fun way and through the eyes of someone who lived through it. … I walked away from that visit thinking, wow, I hope I’m like that when I’m 78, and I hope I’m like that now, you know, just full of life and curious and really just working, just keep working, keep working, stay open. And Les was like that, too, actually. Les stayed curious until the end. I think that’s important.”

The movie was filmed in 2000, but it’s receiving its premiere at the Film Forum some 15 years later. One of the reasons for the delay had to do with Leibrecht’s quest to secure rights to some of Leacock’s film clips. After funding came through, she was able to complete the project.

“I think at the very beginning I wondered how I was going to pull it off without the clips, and I just kept chipping away at it and chipping away at it, thinking about it,” she said. “It’s the thing about filmmaking is you’re still filmmaking even if you’re not sitting at the editing table. You’re filmmaking when you’re washing the dishes. You’re filmmaking when you’re driving to work because your mind is going, you know. So you’re thinking about the project, how can I do this, how can I do that. I figured eventually it would get done, but I didn’t think I would be finishing it without Les, definitely an unexpected twist.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

- How to Smell a Rose: A Visit with Ricky Leacock in Normandy is currently playing at New York City’s Film Forum. Click here for more information.