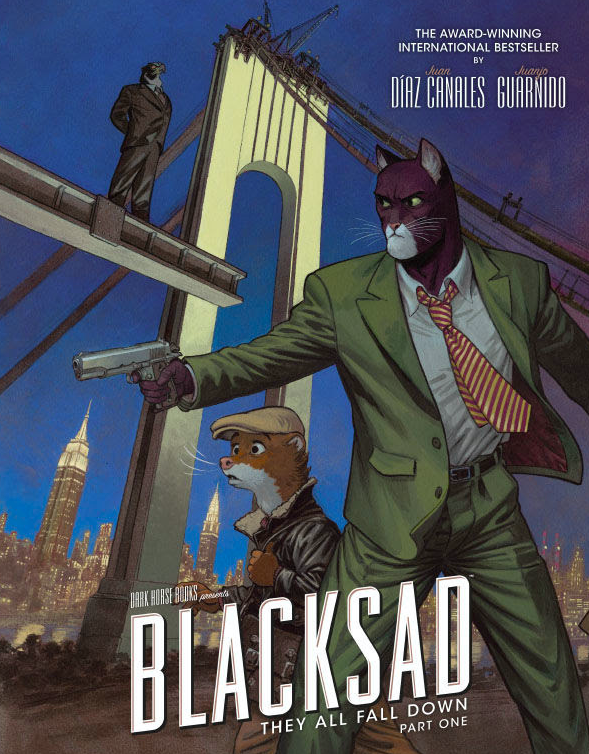

INTERVIEW: ‘Blacksad’ is back with the all-new adventure ‘They All Fall Down’

Image courtesy of Dark Horse / Provided with permission.

John Blacksad is a feline private detective who finds himself in mid-century America, and in his latest graphic novel, he’s taking on a long list of baddies, including mobsters and construction magnate Lewis Solomon, according to press notes. Writer Juan Díaz Canales and artist Juanjo Guarnido first brought Blacksad to comic and graphic novel audiences more than 20 years ago, and after a seven-year hiatus in the United States, Dark Horse is publishing their latest noir adventure: Blacksad: They All Fall Down.

Part One of They All Fall Down is now available, with a second part promised in the future.

Helping the creative team with the translation of Blacksad are Diana Schutz and Brandon Kander. Recently Schutz, a veteran of Dark Horse comics, exchanged emails with Hollywood Soapbox about all things Blacksad and the wonderful world of translation. Questions and answers have been slightly edited for style.

Are you amazed by the continued success of the Blacksad series?

There are so many reasons to love Blacksad that it’s no wonder the series is successful — though it is surprising since there’s really nothing else like it in the comics marketplace. First of all, the art is lush and beautiful: Blacksad co-creator Juanjo Guarnido is a master of watercolor. Nowadays, of course, nearly all American comics are colored digitally, and though computer color has been a huge game-changer for the industry, there’s a sense in which it also mediates between artist and reader, keeping readers at a slight remove, whereas hand-painted artwork brings you right in. You can almost feel the artist’s color brushstrokes on each page, which evokes a kind of expressivity that, I think, digital often precludes. As for the stories, writer Juan Díaz Canales has an obvious passion for mid-century Americana, and the writing focuses on the realities of life 70 years ago — except that everything is filtered through the more enlightened eyes of our hero, John Blacksad. Who, let’s face it, is a pretty cool cat — literally! What’s not to love?!

I should mention, too, that Dark Horse has been very attentive to the book’s production values. In order to best reproduce hand-painted color, among other things, it’s important to print on a thicker, whiter, higher-quality paper stock with a proper matte finish. And the new book, in particular, presented some technical niceties with the cover that required our designer, Cary Grazzini, to be even more adept than he usually is, though that won’t actually become evident until the next volume is printed, wrapping up the current storyline.

What was the experience like, translating this two-part storyline? What’s the process like?

To tell you the truth, it’s been fun! The anthropomorphic characters and the 1950s noir sensibility at the heart of the series appeal to me personally, as a reader. Honestly, I’ve been blessed throughout my career to work on projects that I enjoy, and now that I’m more or less retired, that’s become even more important.

However, Blacksad does represent a unique challenge for translators. Juan Díaz Canales writes the original script in his native Spanish, but French publisher Dargaud is the international rights holder and licensor of the book, meaning that the “official” script is not the Spanish source text but its French translation, which Juanjo Guarnido also reworks to better integrate words and pictures as he’s drawing, since things inevitably change at that stage.

So, in a perfect world, Blacksad translators should have both Spanish and French at their command. My partner Brandon Kander — who, like me, grew up in Montreal — is a French-to-English translator, and he does the initial pass based on the French version with the male inflection that’s essential to old-school crime. Then I come in and write the final script in our target language — English, that is. As I mentioned in the Translation Notes at the back of the new book, I speak French and read Spanish, so I consult both scripts when writing our final version, and where there are differences between the two, or even just shades of difference, I’m in a position as the book’s American editor to choose whatever I feel best serves the English script — always with an eye to making sure that our final text fits the space allotted, as that’s fixed in the original art, and always subject to the creators’ approval, of course.

In fact, the creators are an integral part of our process. The book is now published in 39 (!) countries, so I can’t imagine that Juan and Juanjo are equally active in all the different translations that number represents. But the U.S. market is an important one to them. We’ve worked together now for 10 years, when I first became their Dark Horse editor, on 2012’s Blacksad: A Silent Hell, and they’ve always been tremendously helpful when it comes to clarifying ambiguities or other questions of meaning, which can arise in any script, independently of the language in which it’s written. At the same time, now that Brandon and I have become the Blacksad translation team, Juan and Juanjo have also given us a great deal of latitude with that work, and their confidence is invaluable. It’s not often or even usually the case that translators are able to confer so readily with the original creators.

What are some features of comics editing/translating that many people don’t know or don’t understand?

Wow, great question, but where to begin? Most American comics publishers and many editors speak English only, so they just don’t understand how much writing is involved in translation. Edith Grossman — renowned Spanish-to-English translator of Mario Vargas Llosa and Gabriel García Márquez, among others — explains it this way: “Translating means expressing an idea or a concept in a way that’s entirely different from the original, since each language is a separate system. And so, in fact, when I’m translating a book written in Spanish, I’m actually writing another book in English.”

This is precisely what we do when we translate fiction, which is vastly more complex than translating a non-literary text — like directions or assembly instructions. We’ve all seen those hilarious big fails, usually the result of a translator writing into a nonnative language, which is one widespread misconception about translating fiction. In fact, the translator should always be writing into her native language because she has to have more control over the language of the finished text than any other. The literary qualities of prose are dependent on the language in which they’re expressed: voice, tone, nuance, characterization, flow — these are all verbal functions. They don’t automatically translate over! But because of the ways foreign languages are taught in schools — methods that were devised largely to facilitate grading — most people seem to think that there exists a word-to-word correspondence between any two languages, and that’s just not the way languages operate. Translators work with clusters of meaning — just one reason, incidentally, that Google Translate cannot begin to translate fiction or poetry with any real accuracy, let alone finesse.

For instance, when reworking Brandon’s preliminary script for this new Blacksad book, I made a point to insert animal metaphors where I could. So, the Weasel Mafia ferrets out the drifters, and those drifters are easy to buffalo, Solomon has his enemies eating crow — that sort of thing. I don’t imagine readers will notice, though I do believe that language works at a subliminal level, too, and because the characters are animals, the metaphors just seemed appropriate. But when I discussed this with an editorial colleague, he asked if the metaphors were “in the original script,” which presumes this sort of word-to-word correspondence that we’ve all been trained to believe exists — but doesn’t. Yes, the meanings are in the original, but metaphors are language-based, so I had to come up with them in English. Those English metaphors don’t exist in Spanish or French!

When did you first fall in love with comics?

Oh, a long time ago! I’ve been working in the comics industry since 1978, but I was about 5 years old when I began reading the “kinder, gentler” DC superheroes of the 1960s, including Otto Binder and Jim Mooney’s Supergirl, whose backup stories in Action Comics turned me into a lifelong fangirl.

When you look at the comics landscape in 2022, are you encouraged or dismayed?

Well, both? I suppose I’m dismayed that the monthly floppies still largely focus on violence and objectified women, but I’m encouraged at the wealth of graphic novels — and their diversity of stories — that are now available for reading. I’m also a huge fan of European graphic novels, and much of what is translated is targeted at older readers, which I definitely am now.

What has been your most meaningful project over the years?

It’s tough to pinpoint a favorite — they’re all my children, you know? Probably the four black-and-white themed anthologies that I helmed from 2002 through 2009 are closest to my personal tastes and more meaningful in that sense. Dark Horse editor Daniel Chabon has repackaged three of them in the last couple years: Noir, a collection of crime stories; Drawing Lines, an anthology of female cartoonists; and AutobioGraphix, an Eisner-nominated book of personal, true-life stories by cartoonists who tend not to work in autobio. The fourth anthology, Happy Endings, is in the process of being repackaged with editor Jenny Blenk, and features Mike and Kate Mignola’s “The Magician and the Snake,” the only time I ever worked with my longtime friend Mike, and he won an Eisner Award for that story.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Blacksad: They All Fall Down: Part One is now available from Dark Horse. Click here for more information.