INTERIEW: Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson on his influences, his songwriting, his mouth organ

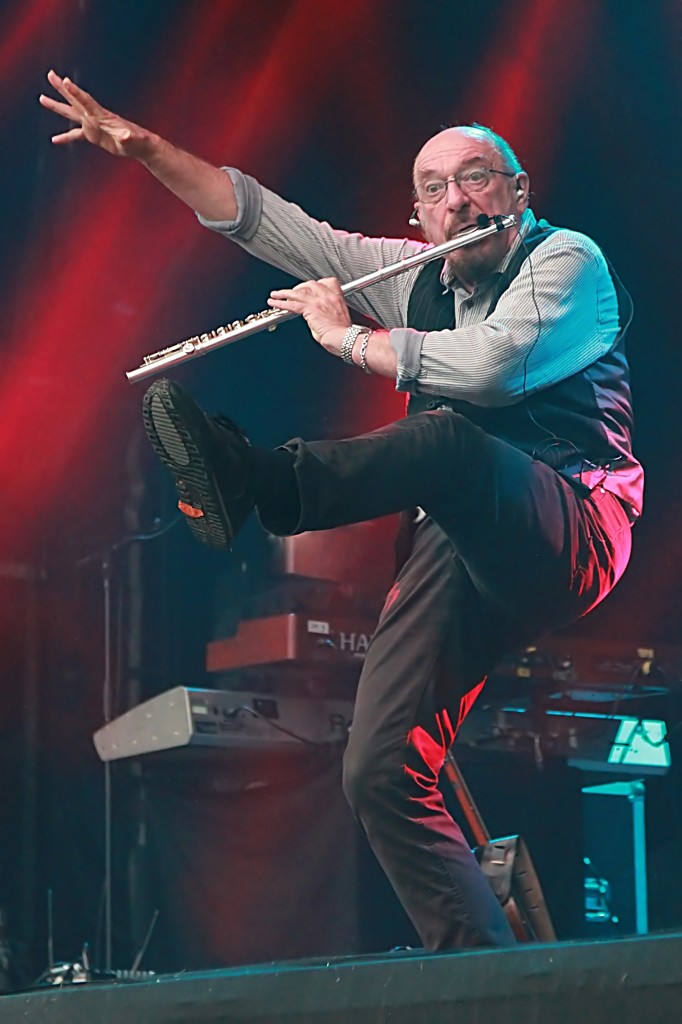

Photo: Ian Anderson is the creative force behind Jethro Tull’s 50th anniversary tour. Photo courtesy of Travis Latam, Windsor / Provided by press page with permission.

Singer, songwriter and flutist Ian Anderson recently celebrated 50 years as the frontman of Jethro Tull, the progressive rock ‘n’ roll band that broke the rules and gathered tons of fans who prefer their music a little offbeat and diverse. Anderson has invited the world to celebrate this golden anniversary by touring Jethro Tull’s music around the globe. He makes a stop Saturday, Sept. 14 at the Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, New York.

“It doesn’t seem like 50 years,” Anderson said in a phone interview earlier this year. “It’s 72 hours since I last played [these songs], so it doesn’t feel like 50 years. … It doesn’t really feel as historical perhaps as it would if I was listening to an early record release of the Rolling Stones or something that is defined in my world by reference to what else was going on in my life at that time and what was going on in the world at that time. It’s with some thought as to that reality that I try to present some of the music that we play on stage because it is trying to set a tone. It is making reference to the times in which Jethro Tull became known and what else was going on in the world — the Vietnam War, for example, the space race, the Cold War years, the cultural changes that came about, the beginnings of big rock festivals and free love.”

The late ’60s, when Jethro Tull formed, was a time seemingly all about sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, but Anderson said most of that image is a fabrication. “Having been on tour with Led Zeppelin, I can assure you a lot of it is just made up,” he said with a laugh. “They were perfect gentlemen most of the time.”

This particular tour is focusing mostly on the first part of Jethro Tull’s existence, stretching back to the very beginning when the band’s name came to the members in January of 1968.

“In the next 10 years, an awful lot happened,” he said. “It was during that decade that Jethro Tull became known from Japan to India to Russia to all of the Eastern Bloc countries during the Cold War years and of course throughout Europe and into the U.S.A., too. So that’s the period where I think most fans got to know about Jethro Tull — the older fans who will have kind of grown up with that music in that era, but even younger fans, people who weren’t born then, who were hearing the music today for perhaps the first time.”

Anderson said it’s difficult to include all of the gems on stage. A two-hour concert can be a lot of things, but it cannot be a full career retrospective. So he needs to make some tough choices.

“You can’t cover the whole thing,” Anderson said. “There’s just way, way too much material, so … probably 80 percent of the music is from that period really between 1969 through ’86, ’87. Most of it falls into that category, but we do include a few things from the very first album as well, which gives me the opportunity to pick up the mouth organ. People to like to refer to it as a harp, which I always found slightly annoying and irritating. The blues harp, or they refer to it as a harmonica, but to me it’s the mouth organ because where I grew up in Scotland, people would play that quirky little instrument, which was called a mouthy. Mouthy as in mouth, mouth organ, so I will still to this day refer to it as my mouth organ.”

A variety of instruments — some of them seemingly out of place in a rock band — has been a hallmark of the Jethro Tull sound. Anderson is known the world over for his flute playing and various time signatures. This uniqueness can be heard on the band’s “Locomotive Breath,” “Bungle in the Jungle,” “Aqualung” and “Thick as a Brick,” among others.

“It always interested me I think as a songwriter to work with other instruments because it does help in that creative process,” Anderson said. “The acoustic guitar is far and away the most common instrument I would use to write a song, but if I sit down with a balalaika or a mandolin, something different is going to come out. If I write songs using keyboards, which I did quite a bit in the ’80s, something different will come out. That’s from a songwriter’s perspective a good way not to just keep repeating yourself doing the things that you always do if you’re overly familiar with a certain instrument.”

He added: “Sometimes just focusing on a monophonic melody, then that makes you consider it in a different way, so that’s why I did it. And I think that was the case probably from early days but particularly toward the end of ’68 when I was working on the songs for our second album, Stand Up. That was when I began to actually not amass but gather around a few other instruments that would perhaps go on to serve me well over the years. Yeah, it’s part of the songwriting experience.”

Growing up in Edinburgh, Scotland, Anderson was a listener of music rather than a player of tunes. In particular, he loved folk music and church music.

“Those were my musical influences and my only influences, but then a curious thing happened in the ’50s, which was the advent of a new relatively easy-to-play and understand music form which was called skiffle,” he said. “And that was in a way bringing back to European shores the music that had been exported a couple hundred years before from Europe, particularly from Scotland and Ireland, but also in the parts of mainland Europe and found its home in the Appalachians as bluegrass. And that then got reimported back into the UK and became known as skiffle, and it was essentially Americanized folk music that had its roots, its origins in Scottish and Irish and European traditional music. And because it was very simple to play, you could pick it up and just learn three or four chords, and you could do it — the same approach that, of course, during the ’70s emerged as punk music. It was the same idea. You didn’t have to be a musician. You just had to know where to put your fingers and play three or four chords and sing enthusiastically, which is what skiffle was about.”

At the age of 12, Anderson moved away from Edinburgh and farther south into the UK because his parents decided to relocate. At age 17 or 18, he began playing music with a bit more finesse, and he quickly became intrigued by American jazz and blues.

“That was the driving force, and then it became a reality when I left art college eventually to try my hand at being a professional musician, which by then was ’67,” Anderson said. “And I swapped my guitar for a flute, which was a pretty good move.”

At the time, he was receiving parental and outside advice that he should stick with school, receive a college degree and attain a proper job. He was told, time and time again, that he could play music in his spare time.

“I think the impatience though of that creative urge that you have, particularly if like many of my peers you had been to art school, then you already had a taste of that creative world in your mid- to late-teens, and you couldn’t wait to get out there and do something,” he said. “And music was so immediate. That’s why I think it appealed to so many art school students of the day, whether they became members of Pink Floyd or the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. You just have to almost look at the great bands of the UK and the ’60s and ’70s. It seemed like all of us went to art school. That’s where we got bitten by that musical and creative bug.”

He said there was a risk of falling flat on his face and being penniless in a few years, so he needed to weigh his decision carefully.

“Are you prepared to take the risk?” he remembers asking himself. “Do you really believe that you have or can develop the talent? And do you want to burn your bridges and not be able to get back there? Or do you keep some options open and stick with it at least long enough to get a pretty good indication that you do have a reasonable shot at some success in the world of music or in acting or in writing or whatever your creative pursuit might be? You’ve got to be careful, and it’s a little nerve-wracking when you leave home and set off into the new dawn and not really having any certainty that it’s going to work out. Of course, it is a little nerve-wracking, but after a few months I thought, well, if I don’t do something really stupidly wrong, there could be a living in this. It could be at least be a job if not a career.”

Anderson’s songs over the years have become rock standards, always with that unique instrumentation and timing. He never intended for any one song to become a hit; they simply developed organically, and he found there was an audience for them.

“I think if you start to write songs with a view to creating popular, well-received, approved material, that’s probably likely to be a bit of a mistake,” Anderson said. “I know there are people who can do that and have done it and make tons of money, but I always thought that it’s better just to write a song that gives you a lot of personal satisfaction and gives you a musical challenge, maybe even an intellectual challenge. It’s something you really want to get your teeth into, and if you start worrying about how other people are going to accept it or like it or how much money it’s going to make for you, then I think you’re setting yourself considerable restraints and preconditions.”

On a few occasions, Anderson did try to get some radio play for some of his tunes. That, of course, is to be expected. One of the first that fit that category was “Living in the Past.”

“I set about doing that as almost a bit of a joke to our manager who asked me to go away and write a hit single and come back the next day,” Anderson said. “So to humor him, I said, ‘Sure, just give me a couple of hours. I’ll get that done.’ So I came back and said, ‘Yeah, I’ve written a song.’ ‘What’s it called,’ he said. I said, ‘It’s called ‘Living in the Past,’ which is about as untrendy a title as I could think of, and it’s in 5-4 time signature. You’ll love it.’ But, of course, I was just kidding.”

The band released the tune a few weeks later, and Anderson was pleasantly surprised that the unconventional song rose to #3 on the UK charts. “Obviously I had done something almost accidentally right in coming up with something catchy that at least had the integrity of being perhaps one of two songs in 5-4 signature which graced the singles charts in my country,” he said. “Sometimes you can do something, and it’s a little bit offbeat, a little bit unusual, but it strikes that chord with people.”

Another song that fits into this conversation is “Bungle in the Jungle,” which Anderson said was not written as a hit single, but something that was simple, charming and repetitive.

“It made it into the more commercial world, but I have to say it’s not something I would want to make a habit of,” Anderson said. “I’m not really that kind of a writer. I think you’ve got to be a little bit selfish as a songwriter and do what really captures your imagination and not really worry about how other people are going to like it.”

These past two years, as the 50th anniversary tour makes its way around the globe, Anderson has been in a place of reflection and nostalgia. He has often thought back to those early days with Jethro Tull, and he has appreciated how the songs continue to touch the lives of many, many fans.

In his recollections he never used the word retirement — not even once.

“When I decided to do this series of tours, which was back in June of 2017, when I took that decision that that’s what I would do in 2018 and possibly beyond, that was not something that I really expected I was going to enjoy,” he admitted. “You get captivated by the possibilities, and it became quite fulfilling to embark upon this tour April of last year. And here we are almost a year later, and we’ll roll on pretty much until the end of this year with concerts in places that we haven’t played so far. So there’s a whole bunch of shows in various countries of the world where we’re going to do the 50th anniversary tour. … Well, of course, we didn’t visit your country until 1969, which is my feeble excuse for calling it a 50th anniversary tour in North America, but also in countries like Germany and elsewhere. Of course, we didn’t go there in 1968. In ‘68, we were mostly playing simply in the UK. In fact, in ’68, as far as I recall we only had one foreign trip, which was to Denmark, so everywhere else came really in ‘69, ‘70, ‘71. I don’t think we went to Italy until ‘71, so I can theoretically quite legitimately play my 50th anniversary tour in various parts of the world for a few years to come, but somehow I don’t think I’ll be doing that.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Jethro Tull, featuring Ian Anderson, will bring their 50th anniversary show Saturday, Sept. 14 to Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, New York. Click here for more information and tickets. Click here for more information on a new Jethro Tull book.