‘A Man Escaped’ is a realistic prison escape movie

Robert Bresson’s simple and effective A Man Escaped is an uncomplicated look at one man’s struggle to escape a Nazi prison in Lyons, France. The 1956 movie, preserved in beautiful black and white, is nothing short of a masterpiece, an intense story stripped of any exaggeration or overly sentimental drama. We’re told that the story is based on real events. This is not how it exactly happened, but it’s probably damn close.

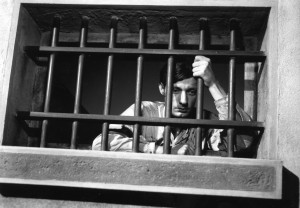

Fontaine (François Leterrier) doesn’t speak much, but we hear his thoughts through a helpful, and never intrusive, voiceover.

He is a man slowly passing the days between his capture and ultimate execution. With each sunrise, he loses a little hope, realizing that the inside of his prison cell may be his last vestiges of home. But the French Resistance fighter doesn’t give up without a fight. Although despair is a daily ritual, he also strives to outsmart the prison guards and devise a plan to escape.

Don’t think that A Man Escaped is some type of Grand Illusion or The Great Escape, two equally impressive movies. It’s not an ensemble piece with rousing music and a cast of colorful characters. Bresson focuses on Fontaine and only Fontaine, with few other distractions. Many of the scenes depict this skinny, innocent-looking man wiling away the time in his cell, thinking of his next plan.

Eventually, the movie catches its stride and Fontaine begins his elaborate ruse to make it out alive. The clock is ticking faster than he’d like: He’s been found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to death.

On the eve of his escape attempt, the Nazis throw a wrench into his plans (not an actual wrench, because that would have been helpful). The solitary man is given a roommate by the name of Jost (Charles Le Clainche), a young man who Fontaine believes is a mole. The added person changes the equation, and now, with only a few hours left to live, our main character needs to modify his plans and lay his trust in the hands of a stranger.

Bresson, who wrote the screenplay based on the memoir by André Devigny, is able to film some beautiful sequences. We first meet Fontaine when he’s being transported in a police car to the prison. The director chooses not to focus on the resistance fighter’s face, but his outstretched hand, which slowly inches toward the door handle and what will prove to be a botched attempt to escape.

Bresson also has a way of hiding the climax of a scene from our eyes. We never find out what exactly happens to Fontaine after he runs from the car in that opening scene, because the camera doesn’t follow him. Instead, we are left looking at his open seat in the car. We can hear gunfire in the distance and shouting, but it takes Fontaine reentering the shot, now with handcuffs, for us to realize what just occurred.

Similarly, when Fontaine works his way through the final escape, there are times when we don’t follow him around dark corners. The camera halts, almost out of fright, and we are only allowed to hear what happens around the bend.

It’s a unique way to show the aftermath of Fontaine’s actions. It’s almost as if the camera is dummying security footage, and it creates an aura of reality.

The movie is also invigorating because of Leterrier’s fine acting. He’s contemplative, smart and quiet, qualities that don’t always translate well on the big screen. This gives the actor the difficult task of filling in the blanks between the pauses with true feelings of dejection, fright and depression.

A Man Escaped doesn’t fit nicely into the sub-genre of escape films, and it’s this uniqueness that sets it apart. It’s an exercise in methodical, careful reality — and that makes for a truly great escape.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com