INTERVIEW: Rick McIntyre’s written saga of Yellowstone wolves continues with 21’s reign

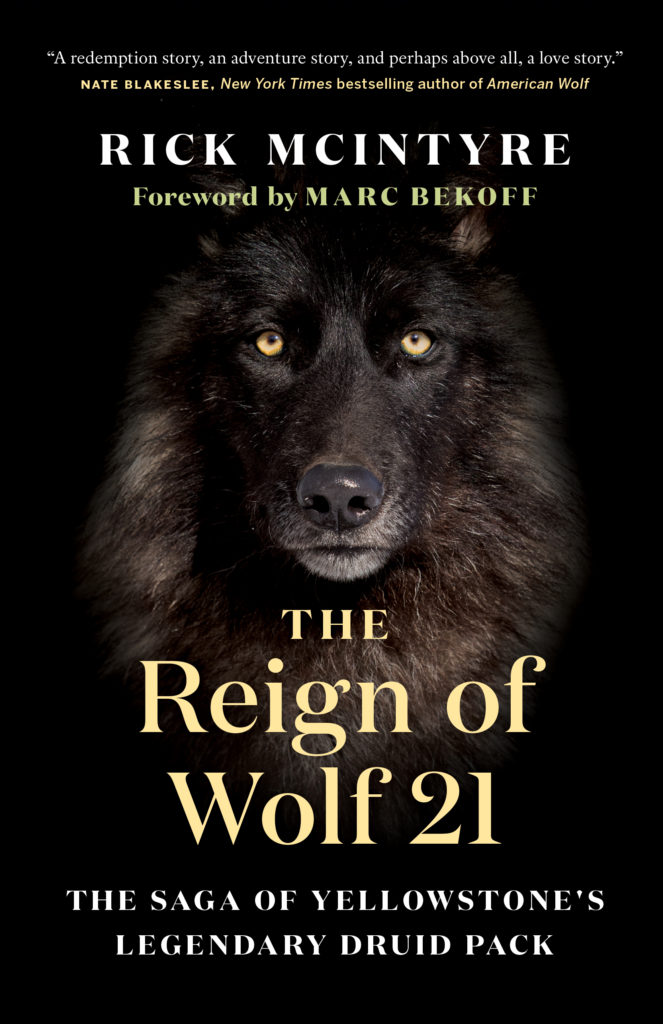

Photo: Rick McIntyre’s new book is called The Reign of Wolf 21. Photo courtesy of Greystone Books / Provided by press rep with permission.

Rick McIntyre is a name well known to wolf enthusiasts and tourists traveling to Yellowstone National Park. For decades he has been a helpful and kind resource for visitors trying to steal a glance of the wolves that call Lamar Valley home in the northeastern part of the park. As a naturalist for the National Park Service, McIntyre’s job was to provide interpretation on many of the Shakespearean canid dramas playing out in the meadows, rivers and mountains of Yellowstone. Throughout the years, he amassed an unparalleled record of locating and viewing these majestic creatures. It’s believed that over the past quarter of a century he had 100,000 wolf sightings. To this day, his mornings are still spent traveling from his home in Silver Gate, Montana, to Lamar Valley to find specimens of this reintroduced species.

When Hollywood Soapbox recently caught up with the naturalist, he had just had a successful morning scoping out the Junction Butte pack in Yellowstone. He has been seeing the wolves in this pack every single day for a very long time. “It’s a very large pack,” McIntyre said in a recent phone interview. “It’s 34.”

When describing the Junction Butte pack, he is quick to point out the bloodline connection to the legendary Druid wolves and the reign of wolf 21, which is the subject of McIntyre’s new book from Greystone Books. The Reign of Wolf 21: The Saga of Yellowstone’s Legendary Druid Pack continues the story from his last book, The Rise of Wolf 8: Witnessing the Triumph of Yellowstone’s Underdog, and there’s a third part in this trilogy scheduled for fall 2021.

“In the heyday of the Druid wolves, which actually covers the time of the reign of 21, in 2001 for a while they numbered 37,” McIntyre said, having committed these details to memory. “I actually did count 37 [Druids] at once as they were traveling together. Later that day, I saw a 38th member of the pack that was separate, so we would say the pack actually numbered 38. And as far as we know, that’s the biggest pack that’s ever been documented. This one here currently is 34, and they’re using Lamar Valley pretty much in the same way that the original Druid pack did, too, meaning that where I saw the wolves today, probably had a count of about 30 this morning, they were within probably less than a mile than when I had that high count of the Druid wolves many years earlier. They are somewhat related to the Druid wolves. It’s a little bit complicated to describe it, but since I’ve been out there pretty much everyday since the Druids numbered that high, I know that some of the younger members at a certain point in the past started a new pack. And some of the wolves that were born into that new pack eventually started this pack that I’m mentioning, so that’s the connection. There is some Druid blood in these wolves here, especially in the pups.”

McIntyre’s recent wolf sightings have been centered on a location approximately 1 mile from the historic buffalo ranch run by the Yellowstone Forever nonprofit in Lamar Valley. In fact, the so-called rendezvous point where McIntyre and other wolf enthusiasts have been tracking the Junction Butte pack is sandwiched between many important geographical locations when considering the history of wolves in this part of the world. Besides the nearness to the Druid’s dominance, the Junction Buttes are also close to where wolves were first reintroduced 25-plus years ago, a high-stakes experiment to return the predator species to the national park where it had once roamed freely before being banished from he landscape (extirpation, or locally extinct).

“All of the wolves that have lived in Lamar Valley, they seem to gravitate to that area,” he said. “There’s several advantages. There’s a river between the road and that meadow, and so that tends to keep people out of the area. They don’t want to cross the water. It’s a crossroads of a lot of animals as they feed and migrate and travel through the area, and that means that there’s all sorts of trails the wolves can take in pretty much all directions if there’s no prey animals right there in the meadow. They can go to other areas and go hunting, so it’s a convenient place.”

McIntyre’s connection to these wolves, and his copious amount of daily notes on their counts and behaviors, was all a bit of an accident. He said his placement on this sacred land, bordering Montana and Wyoming, was purely by accident.

“It’s kind of a long story,” he conceded. “I get into it in the first book, The Rise of Wolf 8, but somehow I ended up here. My background is being a Park Service naturalist. Those are the rangers that do the nature walks, the slideshows, campfire programs, things like that, meaning that my job was to talk to part visitors and explain things to them, so that was my background. I had been around wolves when I worked at Denali National Park for a long time in Alaska, so I was pretty knowledgeable about their behavior. We never really expected that upon being reintroduced into Yellowstone they’d ever be very visible because the wolves that were brought down were from a part of Alberta and then later British Columbia where there was very intensive wolf hunting and trapping. So all the adult wolves were brought down, and it’s very likely that they had family members that were killed by human beings. So that’s why I say they would have reason to be afraid of people, to not want to be seen by people, to want to stay away from roads, anything that had to do with human beings. But somehow after the original wolves were released in 1995, they apparently came to an understanding that Yellowstone was different than where they had grown up, that it was a safer place for them.”

Yellowstone National Park is a large expanse of land, and it’s fairly open for binocular and scope-toting tourists to find wildlife on the distant hills. One can stand in the middle of Lamar Valley, as one example, and literally see for miles and miles in several directions with few obstructions. This means that wolf viewing is optimal as long the creatures are not bedded down behind trees or rocks.

“They chose territories where oftentimes we had good views of them, and Lamar Valley is probably the best example of it,” said McIntyre, whose house is located just about as close as legally possible to this wolf haven. “So I just happened to end up in a situation where day after day I could go out and see these wolves as the years went by, and it’s now been about 25-and-a-half years since the reintroduction started. I’ve been out pretty close to 8,500 days, well over 90 percent of the time that the wolves have been back, and it’s really just a dream come true in terms of anyone that wanted to have an understanding of how wolves behave, what their lives are like, the challenges they face.”

Most importantly, McIntyre and his friends and colleagues have been able to track wolves over the expanse of the canids’ entire lives. That means in the past quarter of a century he has seen wolves be born, grow up, find mates, start to have pups of their own, and eventually grow old and die, sometimes in battle and sometimes of natural causes. Cue The Lion King music because McIntyre has seen the circle of life many times in Yellowstone.

“I would compare it to let’s say anthropologists that perhaps might discover an unknown tribe in the Amazon or something like that, and they spend years studying their culture,” he said. “Another example would be in the Old West where a frontiersman, a trapper, a former soldier made friends with an Indian tribe and lived with them for several decades and then wrote about their experiences. I kind of see myself as being in the same category as that, so in the writing that I do I just try to very simply tell the stories of these wolves that I came to know.”

In McIntyre’s books, the protagonists are the wolves themselves. These wild animals are assigned numbers by the biologists who track their whereabouts and behaviors (nicknames are usually frowned upon by these scientists). The first book centered on wolf 8, an original pup who was brought down from Canada. He later adopted and raised wolf 21, the subject of book #2, which was recently released. The reason for that adoption? Wolf 21’s father had been illegally killed.

“So in the first book I talk about the relationship that those two wolves had, the older male and the younger male, and the second book, The Reign of 21, continues his story,” McIntyre said. “And then the third book, which will be coming out in a year, is on wolf 302. He was 21’s nephew, and his story is very different from the other two main characters in that he just didn’t seem to have the same sense of responsibility or duty that wolf 8 or wolf 21 had. So he was kind of the opposite side of the coin of those two heroic wolves.”

The original plan for McIntyre was to end this “Alpha” series after three books, but as he was penning these pages, an idea for a fourth book emerged. He would love to concentrate his efforts on the female wolves of Yellowstone, who have numerous stories to tell.

“The main characters in the first three books are alpha males, so I’m not sure what the title of the fourth one would be but probably something like Alpha Female,” McIntyre revealed. “And I’m very lucky in that I have the perfect main character for that, that’s the 06 female who was 21’s granddaughter. She was the greatest female wolf that we ever had, so I’ll tell her story and then the story of her daughter. And then just to change the pace a little bit … I’ll also have sidebars that tell the story of our other great and heroic Yellowstone females. You may know that we’ve discovered here that it’s not the alpha male that is the leader of the pack; it’s the alpha female. We think that in the old days, when pretty much all wolf biologists were male, it was a bias, a male bias to assume that the biggest and the toughest-looking wolf in the family would have to be the leader of the pack, meaning the alpha male. But probably the best example of how we figured out that really wasn’t the case was during the lifetime of 21. As I write in that book, he was the toughest wolf that we’ve ever had, a master of fighting, never lost a battle with a rival wolf — but never killed a defeated opponent. We always found that he was big and strong and invincible in battle, but he certainly wasn’t the leader of his pack. It was his longtime mate, 42, so she was really the brains of the operation. And he just worked for her.”

For McIntyre to focus on a wolf for an entire book, that animal needed to have lived a remarkable life. Although he is fascinated by each of the canids he views on a daily basis, he is able to tell the superstars apart based on his extensive field notes. To better understand these protagonists of Lamar Valley, McIntyre offered a metaphor to the human world.

“Now most wolves, like most people, I think it’s fair to say, don’t necessarily over the course of their lives achieve great things,” McIntyre said. “Most wolves and most people live somewhat average lives, and then in both cases with both species there are very successful individuals who have epic lives, very dramatic lives, Shakespearean lives. I don’t know why it was me that ended up in this situation, but somehow it was I who got to witness these lives, in some cases pretty much the entire life of some of these main characters. So I’ve known hundreds and hundreds of wolves over the years, and I have been very fortunate to have these main characters — wolf 8, wolf 21, wolf 302 and the 06 female — that I can build these books with them as the main characters.”

It’s clear that McIntyre himself is one of these individuals who has lived an epic and dramatic life.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

The Reign of Wolf 21: The Saga of Yellowstone’s Legendary Druid Pack by Rick McIntyre is now available from Greystone Books. Click here for more information.

I’ve read Rick’s “Rise of Wolf 8”, and have spent nearly every summer over the past 15 years, seeing and following the Lamar Valley wolf packs. I highly recommend his work to anyone interested in wild America, the grey wolf in particular.

Charles, that you for your comments about Rick and his work. I too, have been visiting Yellowstone since 2005, a few spring/summer/fall visits, but it’s the dynamics of winter that are captivating. February 2021 will be my sixteen visit, and I go with The Wild Side out of Gardiner. This wild world is beyond belief…truly a Nat Geo experience, and Rick has been there every time.

Douglass Smith, NC

I am new to McIntyre’s books, coming to them somewhat circuitously through reading Sy Montgomery’s writing, particularly about the giant Pacific octopus. My husband and I relocated to the Pacific northwest a few years ago, and I have become fascinated by the geography and the wildlife of this region. McIntyre’s writing has opened up a subject that inspires and moves me greatly.