INTERVIEW: ‘Family Pictures USA’ dives deep into country’s shared past

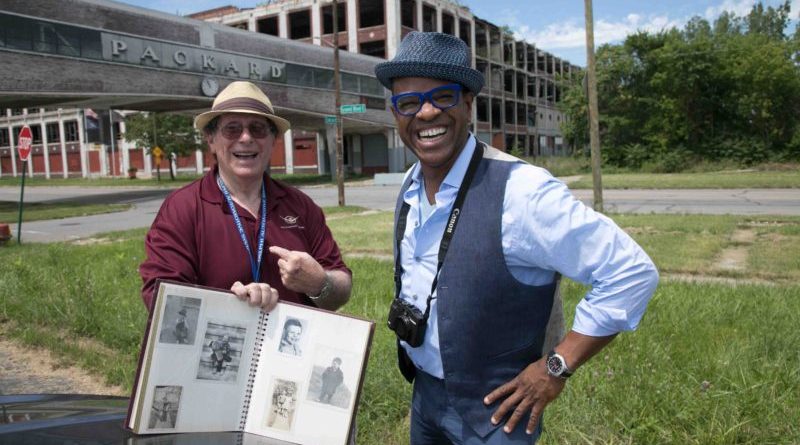

Photo: Host Thomas Allen Harris visits the former site of the Packard Plant in Detroit with Arthur Kirsh to share insights from his family photo album. Photo courtesy of Digital Diaspora Family Reunion, LLC / Provided by CaraMar Inc. with permission.

The family photo album comes into focus on Thomas Allen Harris’ new three-part documentary, Family Pictures USA, airing Aug. 12-13 on PBS. The series goes deep into the stories and lives of American families, and the narrative is built around the memories that are seemingly attached to these collections of snapshots and selfies.

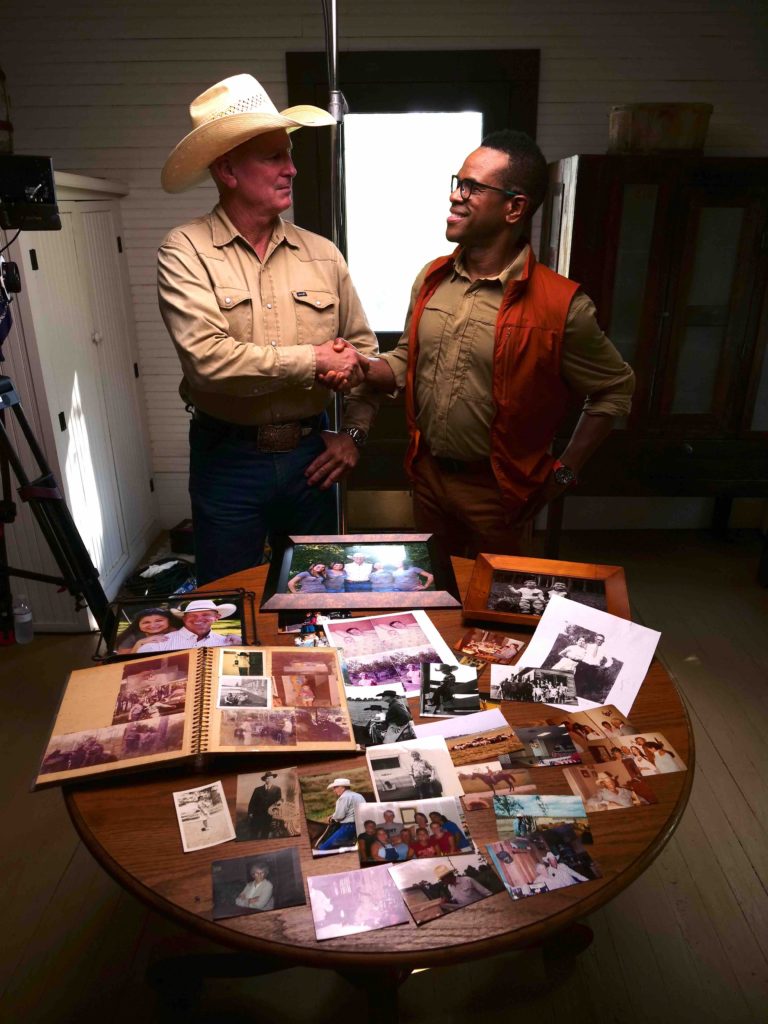

As Harris explores the communities of the United States, he unearths the country’s shared history, common values and diversity. His documentary team travels from the neighborhoods of Detroit to the farm fields of North Carolina, and everywhere in between.

Each episode is structured in a similar way and inspired by Harris’ photographic project known as the Digital Diaspora Family Reunion. The filmmaker, who is from a family of photographers, pulls into town and attends a photo-sharing event. It is here that he initially learns of the setbacks and triumphs of the community members. He then travels deeper into the neighborhoods to learn more about the families and their unique history.

Recently Hollywood Soapbox exchanged emails with Harris about the TV project. Questions and answers have been slightly edited for style.

How did you come up with the idea for Family Pictures USA?

I come from a family of photographers, and I have been consumed with using the family photo album to uncover personal truths about my immediate and extended family. For the past two decades I have used my family album and archive in my film and art making. In fact, I’ve been able to make a living using my family photo album.

But it was one particular film that made me realize the hidden power of the album and transformed my relationship with it.

My late stepfather, B. Pule Leinaeng, left South Africa in 1960 to heed Nelson Mandela’s call to build a global anti-apartheid movement. When he died, I took his family album and photographic archives back to South Africa, reintroducing his story to young people who didn’t know it. Out of that came my film Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela. That was the first time I got a chance to see how family albums could reconnect people with history that deeply affected them.

As I traveled to festivals, people would ask me to create a platform to help them use their family photo albums and archives to tell their own stories, and out of that we created Digital Diaspora Family Reunion (DDFR). DDFR is a socially engaged art project that helped people bring their family stories into a public crowd-generated archive that connected the dots between the personal family archive and the social and cultural history as collected in formal archives. We traveled to over 65+ communities as part of the DDFR Roadshow, holding over 70+ live public events, where over 4,500 people participated and shared over 45,000 images with our production team. It was out of that experience that Family Pictures USA was born.

How did you select the subjects to focus more closely on? Did you decide this at the photo-sharing events?

We use a pretty broad net to find our deeper dive subjects and participants in general. The heart of our process are our relationships with local community organizations who become our local champions. We work with their extensive local roots to generate interest in participating, finding interesting local participants and introducing us to those hidden corners of their communities whose voices might easily be overlooked.

We also do extensive research, using available resources such as local newspapers, magazines, alternative weeklies, visiting local barber shops and listening closely to what locals are saying, stopping in at local coffee shops, diners, communal gathering places and doing a lot of listening and searching for interesting angles on local concerns, trying to find the people who are considered important to local communities, who they value and celebrate and consider to be representatives of their values, experiences and best intentions.

Then we reach out to those people and ask them to share their family stories and images with us. Our pitch is that their stories are important not just to their families, but to their neighbors, and to us as a nation, who need to see and learn from them about what it means to be human. We believe that these family archives are an integral part of our collective social and cultural history, filling in missing blanks in the public record and adding important nuances and perspectives on what we consider ‘History’ with a capital ‘H’.

Our local community photo-sharing events also provide potential avenues to interesting characters and images that deserve a deeper look. You’ll see in the final episodes that the participants from the photo-sharing events act as a chorus to the deeper dive characters, providing important emphasis and putting a button on ideas or themes raised in those longer segments. But the real value of the local photo-sharing events is the fact that we use all of those personal testimonies in our digital content, rolling out short pieces that complement the national episodes and keep the dialogue and conversation going long after the broadcasts.

Were you surprised by what you found out from these families?

We go into each interaction with our participants without any preconceptions. In fact, we make it a point to be a blank canvas so that our participants can fill in the spaces with their own stories and lived truths. So to that extent, we are always, continuously and happily surprised by what people share with us. Those reactions you see on camera are genuine. I really am wowed by what I’m learning from the people who are sharing their family stories with me.

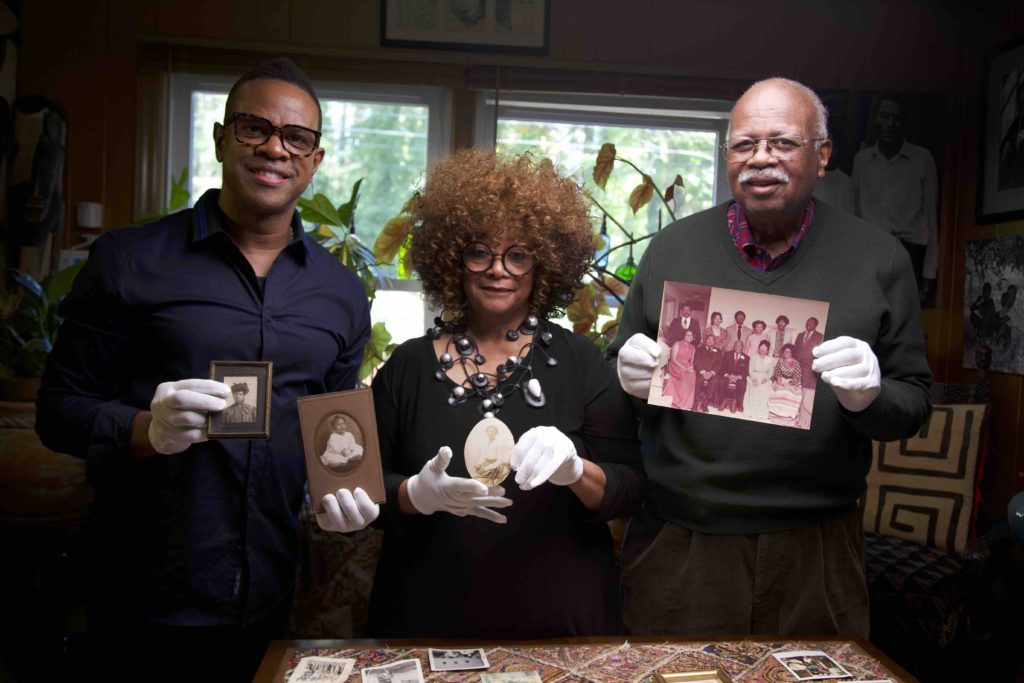

An example …When I sat down with Jaki Shelton Green, from our North Carolina episode, I had no idea that she and her cousin would be telling me the story of their ancestor, Caswell Holt. We knew about the Holt family from our research and how important they were to the textile industry in North Carolina, but after hearing the story of Caswell, we made it a point to find descendents of the Holts and to bring Jaki and them together. It was a revelation of a meeting and I think a really important moment in the story we told of North Carolina.

Are you a big collector of photos and family albums?

Well, as I mentioned we have gathered an archive over 45,000 images that people have shared with us. Our goal is to create a new national family album, where everyone’s story is welcome and where all are placed on an equal footing.

When you start seeing similar themes emerge from the diverse stories you begin to realize the extent to which we have so much in common with each other. We are all keenly interested in celebrating the people we love, the people who love us and capturing the moments that mean so much to us — our anniversaries, our triumphs, our moments of absolute joy … in addition to our remembrances, our sorrows, our regrets. Part of the problem we are dealing with as a society is our ignorance of each other … our lack of knowledge about those we consider ‘The Other.’ But when you see all these images and stories side-by-side, that distance between ‘US’ and ‘Them’ disappears. … We see ourselves in the other, and in so doing our empathy and compassion as one human being for another human being rises. That’s our hope at least.

Do you believe digital photo archives are taking away this pastime and possibly impacting a family’s ability to converse, congregate and tell stories?

Well, actually digital photo archives could potentially be a great aide to our cultural and social history, to the extent that those archives are curated along with the usual historical sources. For the first time, all those selfies and digital images are creating a deep, rich record of who we are and how we live.

But they are also threatened with extinction. We don’t treat those digital images with the same reverence that we hold the old physical artifacts of photos in our family albums. Because they are so ubiquitous, we tend to delete those digital images when we run out of memory on our phones … or lose them when our phone is upgraded … or forget about them on our laptops or hard drives because we aren’t looking at them regularly, like the way we would pull out the family photo album when company or the grandkids come over.

In that way, I think we are in danger of losing the value of our family stories … the family photo album is like a language … if you don’t use it, you lose it.

I think one of the messages from both our DDFR Roadshows and our new TV show is to use the language of our photographic images. To begin to print out some of the more important digital images and record the stories behind them. To make it a multigenerational affair, where children, grandchildren, extended family are engaged in the process of preserving one’s family story and handing it down to future generations.

The New York Times had an article a while back that stated that children who know their family story are better able to overcome setbacks and disappointments in their lives. Knowing how an ancestor got over or made it through similar setbacks improved children’s own resilience. That’s an important lesson that we can all use, and that lesson is told in our family albums.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Family Pictures USA, created and hosted by Thomas Allen Harris, plays Aug. 12-13 on PBS. Click here for more information.