INTERVIEW: Photographer Rosamond Purcell finds beauty in wondrous decay

For some people, a stained, ripped and decaying book is an object to discard, something readymade for the trash pile. For photographer Rosamond Purcell, there’s an aesthetic depth to these books and other found objects, and her sense of discovery and exploration of these items has driven her artistic career. Now, Purcell is the subject of a new documentary from director Molly Bernstein. An Art That Nature Makes: The Work of Rosamond Purcell is currently playing New York’s Film Forum.

Bernstein first connected with Purcell when working on Deceptive Practice: The Mysteries and Mentors of Ricky Jay, a documentary about the famous sleight-of-hand artist. It turns out that Jay is a collector himself, and his dice collection, many pieces made of nitrate, was self-destructing so many years after their creation. Purcell collaborated with Jay on a book about these dice, and the photographer agreed to be interviewed for Bernstein’s documentary on the magician. Although that footage was never used in Jay’s film, Bernstein kept Purcell and her work in the back of her mind and decided that it would be fascinating to direct a feature-length documentary on the influential photographer.

“I went to interview Rosamond about working with Ricky for that film, and that interview didn’t end up in the Ricky Jay film,” Bernstein said in a recent phone interview. “I got to meet her and got to know her work, and I got to see her amazing studio in Sommerville, Massachusetts. So that was really the beginning.”

Purcell said she liked the idea of a documentary about her career, although it wasn’t the initial idea she had in mind. At first, she was thinking about putting together a website to display the many themes she has explored with her work. But, to be honest, Purcell gets rather bored by websites. That’s when Bernstein entered the picture, and the idea of a documentary was born.

“So she had approached us actually about maybe doing a short film for the web,” Bernstein said. “I’ve done a lot of short films about artists and art collectors, so that was the initial idea. But then very quickly once we started, and once I saw the enormous treasure trove of archival material that she had as well as so many incredible photographs, that really made me think, this should be a feature.”

In the film, there are many parts of Purcell’s career on display. One of the most vivid includes her time at a scrap metal business in Owls Head, Maine. Among these many acres of forgotten bits and pieces, Purcell found her muse. She struck up a friendship with the owner of the derelict antiques, William Buckminster, and kept on returning and returning for years to photograph the treasures. The photographs led to the publication of Owls Head: On the Nature of Lost Things.

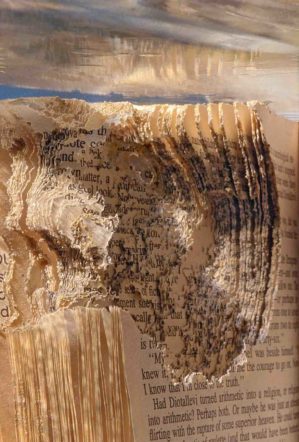

“Well, actually I just went to teach a workshop at the Maine Photographic Workshop, and I’m a person who likes students very much,” Purcell said. “But I don’t like the classroom, and I asked immediately, ‘Do you know of a good cemetery and a good junkyard?’ And they recommended this place, and the minute we drove over, I took one look. And then a student and I found a lot of buried, ruined books right in the front yard, and I was hooked. I mean great, soaring piles of scrap metal, like dinosaur parts. … It’s all about the nature of finding ruined objects.”

In An Art That Nature Makes, Bernstein uses quotes from the Owls Head book, all read by Purcell. Also, the director was able to use Purcell’s own footage of the late Buckminster — Purcell calls him “Bucky” — walking with the photographer over the mounds of captivating destruction.

“Luckily Dennis Purcell, Rosamond’s husband and collaborator, and their son, John Purcell, took video over the years up there and kept it,” Bernstein said. “And so that was one of the amazing things is that we got to discover this footage of a place that is completely gone.”

An Art That Nature Makes runs a quick 75 minutes, so condensing Purcell’s many photographs and themes from a multi-decade career took a lot of careful consideration on Bernstein’s part.

“But in some ways I think the time limit is good because it forced us to really focus on theme, which I think is one of the strengths of the film, that it focuses on themes and ideas,” the director said of the non-chronological nature of the storytelling.

Purcell added: “Also with a chronological profile, if I may say what I think is wrong with that, and why we didn’t do it, is that the audience then hears, ‘And then, and then, and then.’ And they’re already been put on this train somehow that is marked really artificially by years.”

For the photographer, some of the themes of her work are somewhat universal to other artists; however, few people would have found the photogenic treasures that Purcell has found over the years. By spinning a bottle in such a way, she may take a simple picture of text from a book seemingly emerging from a verdant countryside. A bookshelf that holds waterlogged and falling-apart tomes takes on a new interpretative level when seen through Purcell’s lens.

Many of Purcell’s photos are of objects found in natural history collections in the dark corridors of museums. She will click away at skulls, bones, specimens dripping in formaldehyde, holes, imperfections and details that might seem strange to the casual viewer. After the photo is blown up, the artistic merit comes into fine focus.

One of Purcell’s projects from only a few years ago was her collaboration with William Shakespeare expert Michael Witmore. Their book, Landscapes of the Passing Strange: Reflections From Shakespeare, combines Purcell’s photographs with Witmore’s words — all focused on the Bard.

“Michael, who is a friend, called me and said, ‘I really want to do a book with you on Shakespeare,'” Purcell said. “So when I have somebody who suggests something that doesn’t exist in photography, and I am a photographer. I look, and look and look to see if there is some way that I can kind of approach it, and I usually end up by choosing a method that will distort or sort of alter some original material to make it into something that isn’t actually there. And that’s what happened with this project when I found these distorting mercury glass bottles and realized that if I took a photograph of a reflection in it, then it wouldn’t look like a reflection of what was in it, especially if I moved and changed position and put varying shapes. It would keep on morphing the way something would underwater, and that gave me the feeling that it’s really far back in time. And then I was really interested in seeing how many actual scenes from various Shakespeare plays I could work out just by using these fugitive reflections in an unlikely surface.”

She added: “The point is I was working with a really good Shakespeare scholar who has a very good visual sense and self, and really an encyclopedic feeling for all the plays because he’s been teaching it for years, has been teaching it for quite a while to undergraduate and graduate students. But the point is that I mostly did not go out looking for things, on the account of how I haven’t read a lot of Shakespeare in a very long time. I have a simple sense of most of the plays. So I say, ‘I’m going to do Desdemona.’ And then I go out and try, and it was … Mike saying, ‘No, no, that’s not Desdemona. That is the queen from some obscure play.’ And then he would write something about that.”

Bernstein’s approach to documenting Purcell mirrors the photographer’s own work. It’s a simply made film, what Bernstein called a “homemade” documentary. Purcell, similarly, uses a simple camera and natural lighting to depict the objects she finds. “So it’s a very simply made film without a lot of high-tech graphics or techniques or lighting,” Bernstein said. “In a way it mirrors Rosamond’s approach, and I think it works very nicely.”

Purcell agreed that it was the best approach for the film. “I definitely had the feeling that my approach was not particularly outwardly showy, and that goes along perfectly with my longstanding idea that you can take a good picture with any kind of camera,” she said. “The way a photographer looks when they’re working isn’t necessarily the whole story because it’s the camera that’s doing the looking.”

There’s one telling scene in the documentary that perfectly encapsulates the interpretation of Purcell’s work. Because she often photographs objects from museums and scrap-metal yards, there’s a wonderful “found” quality to these “forgotten” pieces. However, many of her photographs take an object that is scientific and elevates it to a new aesthetic interpretation. She might take a femur bone and, after placint it just so, find a new artistic and visual dimension to its look and texture. In the film, a collection manager doesn’t see eye to eye with Purcell on the need to find the aesthetic quality of an object that with a stated scientific purpose.

“As a matter of fact, after we shot that scene, I said to the film people, ‘We got it,’ because this is the story for years,” Purcell said. “I’ve gone into natural history collections and met with a certain, I would say, resistance or skepticism because there are ways in which these specimens should be seen according to science.”

Bernstein concurred that it was a powerful part of the film that summed up so much of the photographer’s career in a few minutes. “For me, that conversation really took on much more meaning when I was editing it because I had the actual photographs that she was taking in the scene,” Bernstein said. “So I thought it was good when we were filming it, but when I got to insert the actual photos that she was trying to get Paul to look at, I was amazed. I just thought it was a tremendous moment.”

In the end, An Art That Nature Makes is about ideas and books. As Purcell put it, the film shows ruined books, new books, the concept of reading across the pages of nature and even a termite-eaten piece of paper. “It’s about the fact that I came from a family where books were honorable and that I found ruined books that I found fascinating,” Purcell said. “It’s about books.”

Bernstein said she appreciated the film’s ability to explore the interesting connection between science and art. “I hope that people reflect because I think it’s a great subject and really worth thinking about,” the director said.

“After all, in the past, scientists needed artists to paint their specimens, to draw their specimens,” Purcell added. “Scientists used to be dependent on people with a pencil and paper.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

An Art That Nature Makes: The Work of Rosamond Purcell is currently playing the Film Forum in New York City. Click here for more information.